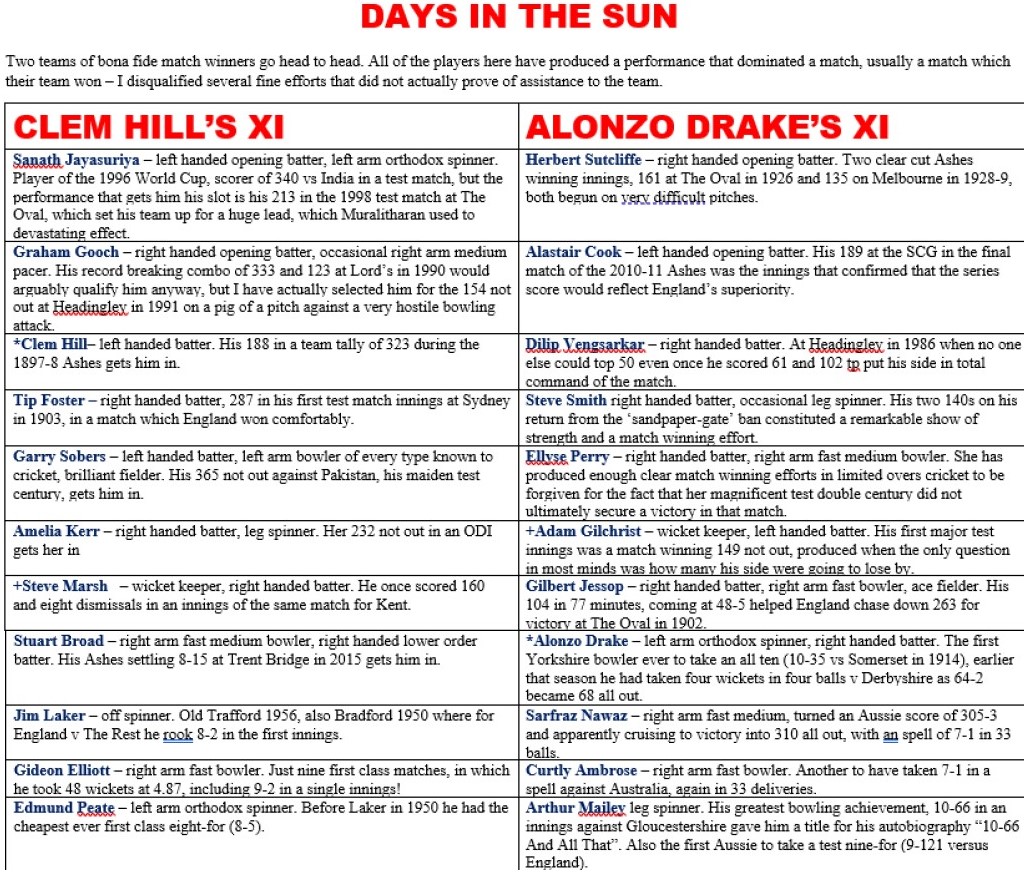

INTRODUCTION

Welcome to my latest exploration of the ‘all time XI‘ cricket theme. Today the focus is on outstanding individual performances, in the main clearly defined match winners, although I allowed myself one exception whose outstanding individual performance came in a drawn match, but was frequently enough the key contributor to victories to qualify. (at least IMO). Our two teams, who will be competing for the ‘Stokes-Botham’ trophy to honour two famous match winners who I neglected to pick, are simply named in honour of their captains.

CLEM HILL’S XI

- Sanath Jayasuriya – left handed batter, left arm orthodox spinner. He was the player of the 1996 World Cup, and his test highlights include a 340 against India. However, the performance that gets him an opening berth here came at The Oval in 1998. Arjuna Ranatunga, one of the outstanding captains of my lifetime, won the toss and put England in on a flat pitch, and England batted decently to record a tally of 445 in the first dig. To give Ranatunga’s decision, taken in order to guarantee his bowling trump card, Muralitharan, got a decent break between what were going to be two long bowling stints Sri Lanka needed a big lead on first innings. Jayasuriya responded to this pressure situation with a rapid 213, the key contribution to a Sri Lankan tally of almost 600, which gave them both enough of a lead to be firm favourites and time to press home the advantage. A refreshed Muralitharan proceeded to slam home this advantage by twirling his way to 9-65 in the England second innings. Sri Lanka won very comfortably, with Muralitharan Player of the Match and Jayasuriya having to settle for an honourable mention (a joint award may have been appropriate on this occasion).

- Graham Gooch – right handed opening batter, occasional right arm medium (and impersonations of more regular bowlers). His record breaking double act at Lord’s in 1990 (333 and 123 in a comfortable victory) might seem the obvious qualifier, but India on that occasion had a bowling ‘attack’ that barely merited the conventional descriptor, and the pitch was flatter than the proverbial pancake. In the Headingley test of 1991 by contrast the pitch was tricky to put it kindly, and the West Indies had a very hostile bowling attack (Marshall, Patterson, Ambrose and Walsh if memory serves). On a pitch which had seen first innings tallies of 198 and 173, and with Ambrose hitting his straps right from the start, Gooch produced an undefeated 154, as England scraped up 252 (Ramprakash and Pringle joint second top scorers with 27 each). The West Indies collapsed in the final innings and were well beaten. This innings by Gooch almost certainly did make the difference between victory and defeat.

- *Clem Hill – left handed batter, brilliant fielder. It was a must-win game in the 1897-8 Ashes, the pitch was ordinary, and with one exception the Australian top order failed badly. The exception was Clem Hill, and with Hugh Trumble playing a stubborn supporting role for 46 in the only really substantial partnership of the innings. Australia reached 323, which put them in control of the match, and Hill’s share was 188.

- ‘Tip’ Foster – right handed batter. Foster played his first test innings at the Sydney Cricket Ground, at the start of the 1903-4 Ashes series. He responded to this initiation by producing an innings of 287 in an England total of 577. The ninth England wicket fell at 447, but Wilfred Rhodes, giving the first major indication of the batting skill that would see him play for his country as a specialist opener only a few years later, scored an unbeaten 40 from no11, helping the last wicket to add 130.

- Garry Sobers – left handed batter, left arm bowler of every type known to cricket, brilliant fielder. When Garry Sobers walked out to bat against Pakistan after the loss of an early wicket at Sabina Park in 1957 he had a few decent knocks to his credit but had yet to go on to the three figure score that would confirm his claims to front line batting status. By the time the next wicket fell two days had gone by, and Comrad Hunte, the batter who was dislodged had scored 260, with the second wicket stand worth 446, just five short of the then test record held by Bradman and Ponsford at The Oval in 1934. Sobers, the century well behind him, continued on remorselessly, taking full advantage of a depleted Pakistan attack. Eventually he went past Len Hutton’s test record inidvidual score of 364 made at The Oval in 1938, and at that point the Windies declared at 790-3. Pakistan, thoroughly demoralized by Sobers’ ten hour display of dominance folded twice to lose to by a huge margin, and Sobers, having turned his first three figure test innings into a then record 365 not out was well and truly launched on the batting career that would ultimately bring 8,032 runs at 57.78 per innings with 26 centuries.

- Amelia Kerr – right handed batter, leg spinner. At the tender age of 17 she belted 232 not out in an ODI, the highest ever by a woman in that form of the game. Thus far this effort remains her only major batting effort, but thanks to it her batting average is ahead of her bowling average (across international formats she averages 24 with the bat and 22 with the ball), and as she is still only 19 almost her entire career should still be ahead of her. Given the dearth of quality spinners in New Zealand if I was put money on a current female player becoming the first to play test cricket alongside the men my £1 would be on her to be the one to do it. I have argued elsewhere the batting does not depend on pure power, but on timing as well, and cited examples of successful batters of diminutive starure, and as a spinner she purveys a type of bowling that is all about craft and guile. In terms of the current Kiwi men;s team, the natural way to accommodate her would be to stick with Watling as keeper and no six batter, play her at no 7, and then bowlers at 8-11.

- +Steve Marsh – wicket keeper, right handed batter. Wicket keepers scoring centuries has only become commonplace very recently, and wicket keepers making as many as eight dismissals in an innings remains a considerable rarity. To achieve both in the same match, as Steve Marsh of Kent did in the 1990s is therefore a truly remarkable double feat. In total during his career Marsh accounted for 737 dismissals and had a batting average of 28, which was very respectable for a wicket keeper in those days.

- Stuart Broad – right arm fast medium bowler. Trent Bridge 2015 saw a combination of a little bit of late movement for Broad, some poor batting techniques from our ‘frenemies’ the Aussies and a couple of superb pieces of fielding which between them amounted to SCJ Broad 8-15, Australia 60 all out and match and Ashes settled on the first morning. The pinchhitter included video footage of this in their post this morning and I recommend you read the post and watch the video.

- Jim Laker – off spinner. He qualifies several times over. At his native Bradford in 1950, for England against the Rest he took 8-2 on the first morning of the match as the Rest were skittled for 27 – and one of those singles was a gift to Eric Bedser, twin brother Alec having purposely moved back a few yards to make it easy for him to get off the mark! Fred Trueman scored the other single and was (no surprise here) unimpressed by the batting of some of his team mates. Then came 1956, with the prologue of 10-88 in the first innings of the Surrey v Australia tour match (2-42 at the second attempt, as Tony Lock came to the party with7-49) and the crushing final act at Old Trafford when his 9-37 and 10-53 (a first class record 19-90 in the match) won the match and the Ashes. England had run up 459 in the first innings, with Peter Richardson and David Sheppard, neither of them absolutely top ranking batters, scoring centuries. After Australia had slipped from 62-2 to 84 all out in the first innings, Colin McDonald batted five and a half hours for 89 in their second, with Jim Burke, Ian Craig and Richie Benaud all also showing fight, while there was a contest between Harvey and Mackay for the most embarrassing pair of spectacles in test history – Harvey bagged his by smashing a full toss straight to a fielder, while Mackay looked a complete novice, and although he survived a few deliveries he did not make contact with any. Four front line spinners operated in the course of this match and three of them had combined match figures of 7-380 for an average of 54.43 per wicket, while the other took 19-90, an average of 4.74 per wicket.

- Gideon Elliott – right arm fast bowler. He was born in Merstham, Surrey in 1828, but played his first class cricket for Victoria, between 1856-7 and 1861-2. In that short span he played a mere nine matches, which brought him 48 wickets at 4.87 each! His most remarkable analysis in this brief but spectacular period was 9-2.

- Edmund Peate – left arm orthodox spinner. The founder of a great lineage – he was thr first of a series of left arm spinners from Yorkshire that continued with Bobby Peel, Wilfred Rhodes, Alonzo Drake, Roy Kilner, Hedley Verity, Johnny Wardle and the last such to play for England, Don Wilson. He began as part of a troupe of ‘clown cricketers’ run by Arthur Treloar but recorded some very serious bowling figures before he had finished, including the innings of haul of 8-5 that earns him his place here. In total he bagged 1,076 first class wickets at 13.43 – he was definitely not just the guy whose wild swing against Harry Boyle condemned England to the defeat that created The Ashes.

This team features an excellent top five, a hugely promising young all rounder, a keeper who can bat and a well varied foursome of bowlers. There are three top line pace/ seam/ swing options with Elliott, Broad and Sobers, while Peate, Laker, Kerr and Sobers represent an abundance of spin options. Now it is time to meet the opposition.

ALONZO DRAKE’S XI

- Herbert Sutcliffe – right handed opening batter. His massively impressive CV includes two clear cut Ashes winning innings. In 1926 at The Oval, with the England second innings starting with a small deficit and on a decidedly unpleasant pitch he and Jack Hobbs each made centuries, Hobbs going for precisely 100, Sutcliffe scoring 161 in seven hours. Thanks to this effort England made 436 in that second innings, and another Yorkshireman, 49 year old Wilfred Rhodes, took 4-44 in the final innings as Australia slumped to 125 all out and defeat by 289 runs. Fast forward two and a half years to Melbourne 1928 and the third match of that Ashes series, with England two up. At the start of the fourth innings England needed 332, and the pitch was so spiteful that with their innings starting on the resumption post lunch there was speculation that England would not even last until the tea break. Actually, the opening partnership was still intact come tea, and as it endured Hobbs decided to send a message that Jardine rather than Hammond should come in at three if a wicket fell that evening (ironically it was Jardine who was despatched to find out what Hobbs wanted). When Hobbs fell for 49 to make England 105-1 Jardine emerged, with the wicket still difficult, and held out until the close of play. The following morning Jardine went on to 33, and by the time he was out the pitch had eased considerably. Herbert Sutcliffe held out until he had reached 135 and England were almost over the line. They stumbled a little in those closing stages, but George Geary finally cracked a drive through mid on to settle the match by three wickets.

- Alastair Cook – left handed opening batter. By the time England and Australia convened at Sydney for the final match of the 2010-11 Ashes Cook had already amassed two big hundreds in the series (a match saving 235 not out at Brisbane and 148 to help set up the win at Adelaide) and had helped, in company with Strauss to ensure that Australia’s first innings collapse at the MCG would be terminal to their hopes, although Trott with a big undefeated century was the batting star of that match. At The SCG Australia had won the toss, batted first and amassed a just about respectable 281, helped by some lusty blows from Mitchell Johnson. Unfortunately, when it came to his main job, with the ball, Johnson was barely able to raise a gallop or indeed hit the cut stuff. Weather interruptions meant that the England response got underway just before tea on day 2. There was less than an hour of day three to go when Cook finally surrendered his wicket for 189, bringing to an end 36 hours of batting for the series, with Australia’s goose well and truly cooked. A first Ashes ton for Matt Prior and some lively hitting from the tail boosted England’s total to 644, ending just before lunch on day 4. By the end of that day Australia were 169-6, and it was all over bar the shouting (of which the Barmy Army provided plenty on that final day). Before Australia’s third innings defeat of the series was confirmed Peter Siddle at no9 managed to be part of Australia’s largest partnership of the match for the second time in successive games, a stinging commentary on the efforts of their ‘front line’ batters.

- Dilip Vengsarkar – right handed batter. The tall Indian averaged 42.13 in test cricket, and especially impressive for a batter of the 1980s, his record was better against the West Indies than it was in general. His ability to handle tough situations was never better illustrated than at Headingley in 1986, on a pitch on which 21 players did not manage a single fifty plus score between them, and Roger Binny, not normally regarded as a frightening prospect with a ball in his hand, claimed seven cheap wickets. In among this low scoring carnage Vengsarkar scored 61 and 102 in a convincing win for his side, which meant that they had won a series in England, for the first time ever.

- Steve Smith – right handed batter, occasional leg spinner. Yes, I know that has batting style, to put it very kindly lacks visual appeal, and there are some who would say that being captain for ‘sandpapergate’ should have finished his career rather than merely interrupting it. However, ill disposed to him though I am, I have to acknowledge the sheer strength of character he displayed in making two 140+ scores on his return to the firing line at Edgbaston in 2019. Moreover that great batting double undoubtedly won the match for his side, and gave them a position of control in the series that, the ‘Headingley Heist’ notwithstanding, they never truly lost.

- Ellyse Perry – right handed batter, right arm fast medium bowler. I am picking her in this team as more batter than bowler, so the performance that officially qualifies her is one that came in a drawn game. However she contributed, often decisively, to a fistful of victories in other formats. The innings in question of course is her remarkable test double century, which overshadowed everything else in that match. Her recent seven-for in an ODI is just one example of an unquestionably match winning effort by her. I suggested Amelia Kerr as a possibility for playing test cricket alongside the men, and although I do not now see that happening for Perry, I refer readers to this post from 2015, in which I suggested an unorthodox solution to Australia’s then middle order woes.

- +Adam Gilchrist – left handed batter, wicket keeper. The most explosive keeper batter there has ever been. His first major test innings, with everyone thinking Australia were beaten was a thunderous 149 not out to win the match for his side, and it is that innings which gets him the nod today – his 57 ball ton at Perth in 2006-7 was scored at the expense of a thoroughly demoralized England who never looked remotely capable of doing anything other than losing that match.

- Gilbert Jessop – right handed batter, right arm fast bowler, brilliant fielder. Until the final innings of the 1902 test match at The Oval he had had a fairly quiet game, managing only 13 in England’s first innings, and his highlight in the field had been a lightning pick up and throw that ran out Victor Trumper at the start of the Aussie second innings. Jack Saunders and Hugh Trumble tore through the top England batting (four wickets to Saunders, one to Trumble to follow his eight in the first dig), and when Jessop emerged at 48-5, with England still needing 215 all most were hoping was that he would provide some fireworks before the inevitable end. 77 minutes later Jessop holed out with 104 to his name, having smashed the all-conquering Saunders out of the attack, although Trumble was still wheeling away at one end. The score was 187-7, meaning England still needed 76, but George Hirst was still there, and Lockwood stayed while 27 were added, then keeper Lilley helped the ninth wicket add a further 34, and the second ‘Kirkheaton twin’, Wilfred Rhodes, emerged from the pavilion with 15 needed for a famous victory. Gradually, amidst huge tension, they inched their way to the target, and it was eventually Rhodes who obtained the winning single. Jessop’s innings would not be approached either for speed or match turning quality in an Ashes match for a further 79 years, until Ian Botham twice took innings that Australia’s bowlers looked like destroying by the scruff of the neck.

- *Alonzo Drake – left handed batter, left arm orthodox spinner. Before World War I abruptly terminated his career Drake achieved some astonishing feats. At Chesterfield in that final 1914 season he and Wilfred Rhodes turned a Derbyshire score of 64-2 into 68 all out, Drake capturing four wickets with successive balls along the way. Against Somerset that year he became the first Yorkshire bowler ever to take all ten in an innings, 10-35, that innings being the fourth successive first class innings in which he and Major Booth (given name, not rank) had bowled through unchanged.

- Sarfraz Nawaz – right arm fast medium bowler. Australia, set 388 for victory, were apparently cruising at 305-3 when Sarfraz prepared to begin another spell of bowling. In his next 33 deliveries Sarfraz took the last seven wickets while conceding a single, and 305-3 had become 310 all out. Sarfraz’s total innings figures were 9-86.

- Curtly Ambrose – right arm fast bowler. The WACA in Perth is not a venue that many visiting sides have fond memories of, though a side equipped with fast bowlers who manage to pitch the ball up rather than being lured into banging it in short by the bouncy nature of the surface are less likely than most to suffer there. In the 1992-3 series when the West Indies visited Australia reached the hundred with only one wicket down, and the script looked like being adhered to. Then Curtly Ambrose produced a spell of 7-1 in 33 deliveries, and Australia ended with a total of about 120, and the West Indies did not let this amazing spell go to waste – they won comfortably.

- Arthur Mailey – leg spinner. During the 1920-1 Ashes, won 5-0 by Australia, he captured 36 wickets, becoming the first Australian to record a nine wicket haul in a test innings (9-121). Australia then travelled to England for the 1921 season. Their tour match against Gloucestershire seemed to be going fairly uneventfully, with Mailey having a couple of tail end wickets in the first innings, when in the second innings skipper and fellow leg spinner Armstrong tossed the ball to Mailey, saying “see what you can do against the top order this time.” Mailey responded by bowling right through the Gloucestershire innings, recording figures of 10-66, which gave him the perfect title for his autobiography “10 For 66 And All That”.

This team has a solid looking top four (that opening pair could certainly be expected to take a lot of shifting!), a couple of quality all rounders, a great keeper batter and a fine foursome of bowlers. It lacks an off spinner, but apart from that the bowling, with Sarfraz Nawaz, Curtly Ambrose, Gilbert Jessop and Ellyse Perry to bowl pace and Alonzo Drake and Arthur Mailey as spin options looks deep and varied.

AN EXCLUSION EXPLAINED

Many will have their own ideas as to who I should have included, and you are welcome to post comments to that effect. However, rather than doing a long list of honourable mentions I am going to explain one exclusion which will undoubtedly have upset some. Brian Charles Lara twice set world record test scores, 375 and 400 not out, ten years apart at Antigua, and scored a world first class record 501 not out v Durham. The problem is that all three of those games were drawn, and the Warwickshire performance and the second test performance were noteworthy for Lara’s obsessive pursuit of the record over and above all other considerations, to the extent that he actually asked Warwickshire skipper Dermot Reeve not to declare because he wanted the record.

THE CONTEST

The contest for the Botham-Stokes trophy looks like being a cracker. I would expect it to go to the wire, and I cannot predict who would emerge victorious.

AN APPEAL AND PHOTOGRAPHS

I have introduced my two teams for ‘Days In The Sun’, contending for the Botham-Stokes trophy, explained one high profile omission, and this post is already on the long side, so I am holding back a few things I intended to include until tomorrow. However, as some readers will be aware, my mother has recently started a blog. She has as yet no home page, and wants to rectify the omission. I have given her some advice on how to create one, and knowing how collaborative wordpress can be at its best I now ask people to visit my mothers blog, starting with today’s post, and comment there with suggestions for her home page. Now it is time for my usual sign off…