Today I present an all time XI of cricketers whose given names all begin with the letter M, and an honourable mentions section of more than usual importance. I also have plenty of photos to share.

THE XI IN BATTING ORDER

- *Mark Taylor (Australia, left handed opening batter, captain). The second in a sequence of extraordinarily successful Aussie skippers, in that role he consolidated the achievements of Border who had taken over a team of also rans and passed his successor a team of champions and was succeeded by Steve Waugh. The wheels eventually came off the Aussie juggernaut under Waugh’s successor as skipper, Ricky Ponting, who suffered three Ashes series defeats, the last of which featured Australia on the wrong end of three innings defeats. His status as a batter was first shown in 1989 when he scored 839 runs in that year’s Ashes, a series tally beaten by only one Australian (Don Bradman, 974 in 1930), and bested by only Hammond among England players (905 in 1928-9). Probably his most famous moment came when he declared with himself on 334*, at the time a joint record individual score for an Australian with Don Bradman.

- Michael Slater (Australia, right handed opening batter). An attack minded opener who once scored 123* in a total of 184 all out, a performance that almost certainly won his side the match in question.

- Mahela Jayawardene (Sri Lanka, right handed batter). One of his country’s finest ever batters. He once scored 374 against South Africa, a test record for a right handed batter, in the course of which he shared a third wicket stand of 624, a first class record for any wicket, with Kumar Sangakkara. Almost 12,000 test runs at 49 show that he was far from being the Colombo specialist he was sometimes labelled.

- Martin Crowe (New Zealand, right handed batter). With the greatest of respect to Kane Williamson who has been part of a much stronger batting line up, he was probably the greatest batter his country has produced to date. His maiden test century, against England in the 1983-4 series between the two countries inspired his team mates to save a game in which they looked well beaten for most of the duration. This result in turn helped New Zealand to win a series against England for the first time ever, a feat they then repeated in England two and a half years later.

- Martin Donnelly (New Zealand, left handed batter). When he was in his prime cricket in New Zealand was almost entirely amateur, a fact that caused him to leave the game early, taking up a post as marketing manager at Courtauld’s of Sydney. In his brief career he became one of only two players to score Lord’s centuries in a Varsity match, a Gentlemen versus Players match and a test match. The last of this trio was an innings of 206. Also in a now legendary match between England and the Dominions, again at Lord’s, he was one of two Dominions players along with Keith Miller to score centuries, while a banquet of batting was completed by Hammond who scored twin tons for England.

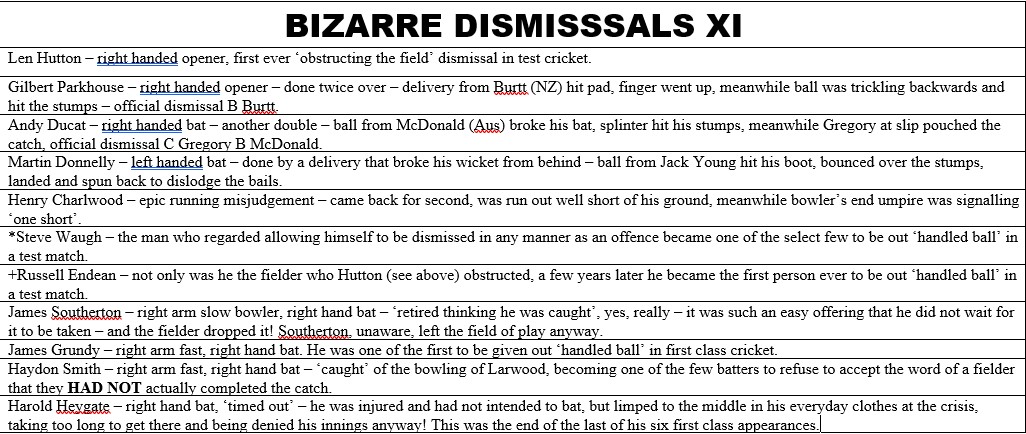

- Mulvantrai Himmatlal ‘Vinoo’ Mankad (India, right handed batter, left arm orthodox spin bowler). This is probably the most controversial selection of my XI, but this guy was a lot more than the first to run out a non-striker for stealing ground in a test match – he completed the double of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets in his 23rd test match, a mark bettered only by Ian Botham (21 matches) ever since. His batting highlights included four double centuries, while his best test innings figures were an eight-for.

- +Mark Boucher (wicket keeper, right handed batter). Over 500 test match dismissals in the course of his very long career, and good enough with the bat to average 30 at test level.

- Malcolm Marshall (West Indies, right arm fast bowler, right handed batter). For my money the greatest fast bowler of the golden age of West Indies fast bowling, and therefore by definition among the greatest of all time. He was also a useful lower order batter.

- Mitchell Johnson (Australia, left arm fast bowler, left handed batter). This was another close call, the other candidate for the left arm fast bowler’s slot also being an Australian with the given name Mitchell, but my reckoning is that Johnson had a higher ceiling than Starc, and for that reason he gets the nod.

- Michael Holding (West Indies, right arm fast bowler, right handed batter). “Whispering Death” first gained legendary status at The Oval in 1976, when he conjured 14-149 (8-92 and 6-57) out of one of the flattest pitches imaginable, a surface on which every other bowler in the match took exactly as many wickets between them as he managed on his own, and he never lost the status he gained then for the rest of his playing career, also going on to a successful commentary career once his playing days were done.

- Muthiah Muralidaran (Sri Lanka, off spinner, right handed batter). More test wickets than any other bowler, 800 in 133 appearances at that level. In 1998 at The Oval, on a pitch that was flat to begin with and never turned truly spiteful he collected 16 English wickets across the two innings, a performance that separated the sides.

This side has a strong top five, a great and often underrated all rounder st six, one of the finest of all keeper/ batters and four mighty specialist bowlers, of whom three are definitely capable of chipping in with the bat as well. A bowling attack of Marshall, Holding, Johnson, Muralidaran and Mankad should never struggle unduly to take 20 opposition wickets.

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

I will deal with some obvious controversies first, starting with…

THE NUMBER SIX SLOT

Two big names missed out here. Mike Procter, the South African genius whose international career was cut short by the enforced isolation of his country would be the choice of many, but I wanted a spin bowling all rounder, given the pace bowlers who were already inked in further down the order, and although Procter did have spin in his locker it was off spin, and I had an off spinner marked for inclusion as well. Mushtaq Mohammed, the Pakistan leg spinning all rounder who made his test debut at the age of 15 was another possibility, and I would not argue with anyone who picks him ahead of Mankad – my verdict went to the Indian who deserves better than to remembered for his association with one particular mode of dismissal.

NUMBERS FOUR AND FIVE

Martin Donnelly’s left handedness secured him the number five slot for reasons of balance. This left a big call to made at number four between two antipodeans who both graced that slot at test level, and Mark ‘Afghan’ Waugh missed out in favour of Martin Crowe. Again, this was a very close and possibly controversial decision, and I accept that those who favour ‘Afghan’ have a valid point of view.

THE OPENERS

The fact that I wanted Mark Taylor to captain the side dictated the selection of the left handed opener, and I like a left/ right opening combo if possible, which led to the selection of Slater as Taylor’s opening partner, a role he actually played. Matthew Hayden had a serious claim on the left handed openers slot but for the need for a captain, and Marcus Trescothick was also in the frame.

OTHER HONOURABLE MENTIONS

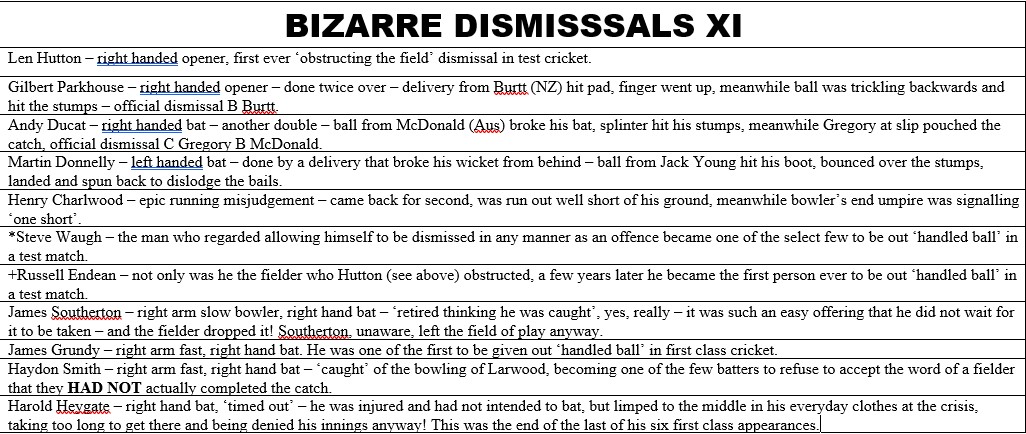

Michael Vaughan was another candidate for captain, but his natural slot in the order would be number three and that would mean dropping Mahela Jayawardene. Misbah-ul-Haq would also have his advocates for the captaincy role, but the only player I could have dropped to make way for him would have been Martin Crowe. Mansoor Akhtar had a good record in domestic cricket in Pakistan, but never delivered in international cricket. Mitchell Marsh of Australia would be one of the first names on the team sheet for a limited overs XI, but his test record is nothing special. Madhusudan Rege had his moments in Indian domestic cricket, but played at a time when conditions in that country were preposterously favourable to batting, and was a one=cap wonder at test level. Marizanne Kapp came closest among female players to challenging for a place in this XI. Mushfiqur Rahim, who recently made history as the first Bangladeshi given out for handling the ball (a dismissal along with the former ‘hit ball twice’ now lumped in under Obstructing the Field) was a potential rival to Boucher for the gauntlets, but I rate the Saffa as the finer keeper and reckon that this side is strong enough batting wise that the extra five runs or so per innings that Rahim might be worth would be unlikely to make a lot of difference. Mushtaq Ahmed, the Pakistan leg spinner of the 1990s and early 2000s, came very close, and if the match were being played at the Narendra Modi stadium I might drop Holding and go in with just Marshall and Johnson to bowl pace and spin trio of Muralidaran, Ahmed and Mankad. Moeen Ali would merit consideration for a limited overs XI, but does not qualify for an XI picked with long form cricket in mind – the notion that the extra batting he offers might even come close to compensating for the gulf in class between him and Muralidaran as bowlers is frankly risible as far as I am concerned.

PHOTOGRAPHS

Today’s photo gallery comes in two parts. First we have some pictures from the place where the West Norfolk Autism Group committee had their Christmas meal earlier today…

…and we finish with some of my usual pictures.