INTRODUCTION

Yes folks, it is time for another variation on the ‘All Time XI‘ theme. Today the focus is on people who produced particularly special final curtain calls. This is an all Test Match XI, and I follow it with a couple of honourable mentions, and then a piece that touches on a topic that a couple of my XI had more than a little to do with – The Follow On. Scene setting complete it is time to introduce the…

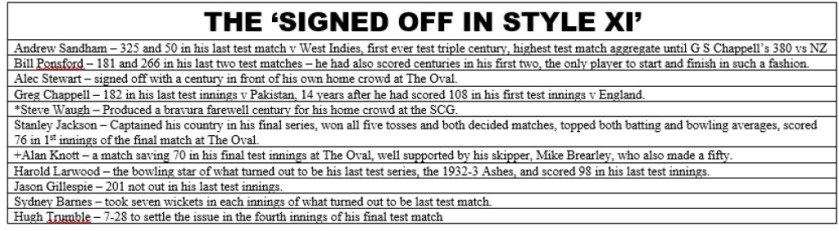

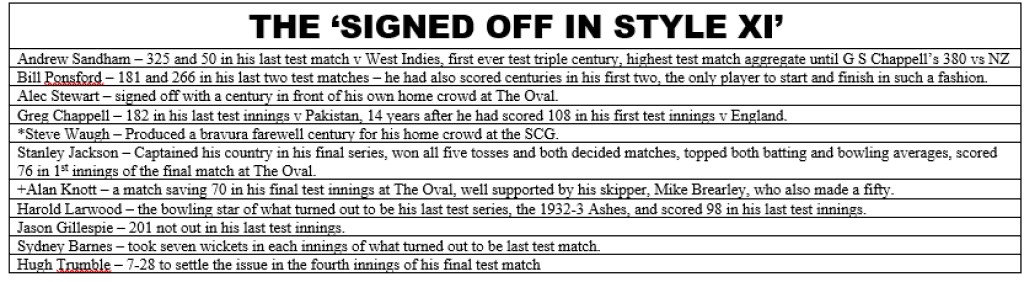

‘SIGNED OFF IN STYLE’ XI

- Andrew Sandham – his last test match took place in Kingston, Jamaica in1930. He scored 325 of England’s first innings 849 (both of them records at the time, his innings being the first test score of over 300, relieving Tip Foster with his debut 287 of the record), and then when skipper Calthorpe decided that as it was a ‘timeless’ match he would not enforce the follow on, in spite of having an advantage of 563 on first innings, Sandham scored a further 50 as England scored 272-9 declared. His aggregate of 375 was a record for a test match until Greg Chappell tallied a total of 380 for Australia v New Zealand about half a century later. Sandham (Surrey) was the in many ways the southern equivalent of Percy Holmes – one half of a tremendously successful county opening pair who did not get the opportunities at test level – their county opening partners Herbert Sutcliffe and Jack Hobbs, test cricket’s greatest ever opening pair, getting the nod most of the time, and quite rightly. Nevertheless, Hobbs and Sandham gave their county a century start 66 times in all (as opposed to the 69 by Sutcliffe and Holmes for Yorkshire). Sandham was involved with Surrey in various capacities for over six decades. It was typical in a way of his unobtrusiveness that his hundredth first class hundred came not at one of cricket’s big showpiece venues but at humble Basingstoke. Sandham was 39 at the time of his last test bow, a mere pup compared to his opening partner in that game, 50 year old George Gunn.

- Bill Ponsford – the stocky Victorian scored 181 at Leeds in the 4th test of the 1934 Ashes, a game which was drawn due to the weather. With the series tied, the final game at The Oval was decreed to be timeless, and when Australia won the toss and batted they needed to get some serious runs on the board. Helped by Bradman (244) in a second wicket stand of 451, Ponsford produced an innings of 266, the Aussie score when he was finally dislodged reading 574-4. Australia went on to 701, and after declining to enforce a follow on, won the match by 562 runs, as skipper Woodfull regained the urn on his birthday, for the second time in four years. That was Ponsford’s swansong, and he had announced his arrival at the top level eight years and a bit previously with tons in each of his first two test matches, the only person to have both started and finished his career in such fashion. It says something about the nature of Aussie pitches of the period and timeless matches, then in vogue in Australia, that Ponsford averaged 84 in the Sheffield Shield but only 48 in test cricket.

- Alec Stewart – as a Surrey native, Stewart had an easy way to take his final test match curtain call in front of a home crowd – retire at the end of a test summer, which is what he did. He treated his home crowd to wonderful farewell century, finishing with a tally of test runs, 8.463, that had an interesting symmetry with the digital representation of his 8th April, 1963 birthdate – 8.4.63! Although I named as wicket keeper in order to fit him into my Surrey all time XI, the truth is that Stewart the specialist batter was about 15 runs an innings better than Stewart the keeper, and as an excellent player of quick bowling who was an uncertain starter against spin, a top order slot makes sense for him.

- Greg Chappell – the 6’4″ South Australian (one of a number of distinguished cricketing products of Prince Alfred College, Adelaide dating back to Joe Darling and Clem Hill in the late 19th century) produced a score of 182 in his final test innings against Pakistan in 1984. 14 years earlier, at the WACA, he had scored 108 in his first test match innings, and barring the quibble-cook exception of Andy Ganteaume whose first and last test innings were one and the same, no one else has centuries in their first and last test innings.

- *Steve Waugh – being a native of NSW, Steve Waugh was in a position to script the fairy tale ending to his illustrious career – has final test match was the last match of a triumphant Ashes series and took place on his own home ground, the SCG. He supplied the last ingredient needed to complete the recipe – a bravura century brought up off the final ball of a day’s play. The tension in the closing overs of that day, as Waugh got tantalisingly closer and closer to the landmark was really something.

- Stanley Jackson – the Yorkshireman was 35 years old (the same age to the day as his opposite number Joe Darling) when he captained England in the 1905 Ashes series. He won all five tosses in that series, England won both the matches that had definite results, and Jackson topped both the batting and bowling averages for the series (70 and 15 respectively). In the final match he contributed 76 with the bat. It would be 76 years before an England all rounder next dominated an Ashes series in such a way – and his golden period came only after he had resigned the captaincy just before he got pushed.

- +Alan Knott – the keeper who had declared himself unavailable for tours was brought back at Old Trafford in 1981, and contributed 59 to an England win. Then at The Oval, with England in serious danger of defeat he signed off with a match saving 70, well backed by his skipper Brearley who also scored a fifty. At the time of his retirement he had made more dismissals – 269 (250 catches and 19 stumpings) than any other England wicket keeper. He had also averaged 32.75 with the bat for his country. He subsequently (in my opinion at least) blotted his copybook by going on the first ‘rebel tour’ of apartheid South Africa, but his test farewell was splendid.

- Harold Larwood – the bowling star of the 1932-3 Ashes, which also turned out to be his last test series. In the final game he scored 98, before injuring himself while bowling. Skipper Jardine made him complete the over, and then kept him out on the field while Bradman was still batting. When Bradman was out, Larwood was finally allowed to leave the field, so the two greatest antagonists of the series departed the arena at the same moment. I have mentioned his subsequent shameful treatment by the powers that be in other posts.

- Jason Gillespie – sent as nightwatchman he scored 201 not out in what turned out to be his last test innings. This ended his career on much higher note than had looked likely when in the 2005 Ashes he bowled largely unthreatening medium pace, paying out over 100 runs per wicket and looking every inch a spent force.

- Sydney Barnes – The England ace took seven wickets in each innings of the fourth match of the 1913-4 series in South Africa. That brought his tally for the series to 49, and his overall test tally to 189. He then quarrelled with management over money and refused to play the final game, otherwise, such was his hold over the South Africans that it is likely he would have had 60+ wickets for the series and been the first to reach the landmark of 200 career test wickets (in what would have been only 28 games). Still, one match earlier than ought to have been the case, Barnes had produced an appropriate swansong performance to confirm his status as the greatest bowler the game had ever seen.

- Hugh Trumble – in the final innings of his final test match he bowled his team to victory by bagging 7-28, bringing his tally of Ashes scalps to 141, which remained a record for over 77 years until Dennis Lillee overhauled it at Headingley in 1981.

This XI has a splendid top five, including a tough and resourceful skipper, an all-rounder at six, a splendid keeper/batter at seven and four front line bowlers of varying types.

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

I am limiting these to two, who I think demand explanation, although one was a first class rather than a test farewell. I start with…

SIR ALASTAIR’S SWANSONG

In 2006 Alastair Nicholas Cook announced himself at test level by scoring a fifty and a century versus India. 12 years and 12,500 test runs later the Essex left hander signed off by scoring a fifty in the first innings and a century in the second at The Oval – against India, for a neat dual symmetry. So why have I not included him? Well, my XI includes a top three who were all regular openers, the performances of Sandham and Ponsford in their sign off matches (remember the name of the XI) commanded inclusion, and in spite of the fact that a left handed batter would have been useful I could not place Cook’s sign off effort above Stewart’s home ground century. Also I could not miss the opportunity to include Stewart in his optimal role as a specialist batter. Finally, I wanted a stroke maker to follow my opening pair. Additionally I was slightly disappointed by the timing of Cook’s announcement of his plan to retire. England were struggling to find folk to open in test matches as the summer of 2018 drew its close, with Stoneman already having been found wanting and Jennings blatantly obviously being in the process of being found wanting. I envisaged, as I wrote in a post at that time, Cook staying on for one last tilt at the oldest enemy in 2019, and helping to usher through two new openers, Burns (who had made an irrefutable case for selection by then) and another (my suggestion, to alleviate concern over having two openers with no international experience, was that England should indulge in a spot of lateral thinking and invite Tammy Beaumont to take her place alongside the men). Thus, while I concede that there is a strong case for Cook having a top three place in this XI, I conclude (a bit like the umpire in a festival match who responded to an appeal against WG Grace by saying “close, but not close enough for a festival match”) that it is not quite strong enough, especially with the most likely drop being Stewart.

HEDLEY VERITY’S LAST BURST

In August 1939, as the warmongers mobilized, Hedley Verity played in Yorkshire’s last championship fixture of the year at Hove. In one final spell of left arm spin wizardry he captured seven Sussex wickets at a personal cost of nine runs. Four years later Captain Verity of the Green Howards was hit by sniper fire as he led his men towards a strategically important farmhouse on Sicily. He was moved to a military hospital at Caserta but died of his wounds at the age of 38. Although his story is a poignant one, and an extra spinning option would have appealed to me, I decided that it would be out of keeping to an include him in an XI picked for their test match sign offs. It is more than likely that had he survived the war Verity would have carried on playing, and I suspect that had been in the test side at Headingley in 1948 Australia would not have been able to chase down 404 on a wicket that was taking spin. It is even possible, without allowing him to break his great forebear Wilfred Rhodes’ record for being the oldest to play test cricket to imagine a 51 year old Verity being Laker’s spin twin in the 1956 Ashes rather than Tony Lock. His 1,956 wickets at 14.90 in less than a full decade of first class cricket show him to have been a very great bowler indeed, which is backed up by Bradman’s acknowledgement of precisely one bowler he faced as an equal: Hedley Verity.

TO ENFORCE OR NOT TO ENFORCE,

THAT IS THE QUESTION

This is a thorny question, and I tackle it here because of the presence in my XI of Sandham, who played in a match that was drawn after a refusal to enforce, Ponsford who played in several matches where the follow on was not enforced with varying degrees of success and Jackson who played a role in the enforcement of the follow on becoming voluntary.

A POTTED HISTORY OF FOLLOW ON REGULATIONS

While the margin required to enforce the follow on changed over the years, being as low as 80 at one point and climbing by stages to 150, until the 1890s it was compulsory to enforce it. Then there was a Varsity match in which Stanley Jackson (son of Lord Allerton, and never anyone’s idea of a rebel) deliberately orchestrated the giving away of eight runs so that his opponents would not follow on. It backfired – set 330 in the final innings the dark blues chased them down, but the lawmakers got the message after years of tampering with required margins that what people wanted was the right to choose.

FOLLOW ON HAPPENINGS

Three test matches have been won by a side following on – Sydney 1894, when enforcing was compulsory, Headingley 1981 and Kolkata 2001. The Sydney match, in which no decision over whether to enforce could have been made anyway, was largely lost on the fifth evening, when Giffen decided to block until the close, keeping wickets in hand for the morrow. Australia ended that day 113-2, needing just 64 for more to win. It rained overnight, though Bobby Peel, who seems to have had a Flintoffesque capacity for unwinding at the end of a day’s play apparently did not hear it. The combination of overnight rain (remember, uncovered pitches in those days) and a hot Sydney sun turned the pitch seriously nasty, and Australia fell to the wiles of Peel and Briggs, losing eight wickets for 36 runs (Darling, the other not out overnight batter, began with some big hitting, but was caught in the deep with the score at 130, and thereafter it was a complete procession). Additionally, during the England second innings the Aussies lost a bit of discipline in the field – both Francis Ford (48) and Johnny Briggs (42) offered easy chances that went begging. At Headingley in 1981 Ian Botham and Graham Dilley did not initially believe they could make a contest of it, and England’s great revival began as a slogfest. Australia had some undistinguished moments in the field, but the crucial period of play happened just before lunch on the final day. Australia were 56-1 with the interval not long away, when Willis was given a go from the Kirkstall Lane end to save his career. In the last stages of the morning play Trevor Chappell could not get out of the way of a bouncer and gave an easy catch, Kim Hughes and Graham Yallop fell to fine catches by Botham and Gatting respectively, and at lunch Australia were 58-4, and suddenly thinking about defeat as a real possibility. Even if Australia had scored no runs at all in that last period before lunch it is hard to imagine that a lunch score of 56-1 could have given them collywobbles to quite the same extent. The third match, which I mentioned in yesterday’s post, was turned on its head by an amazing partnership between Dravid and Laxman, and is the only one of the three where you can seriously argue that the decision to enforce the follow-on contributed to the defeat. At the end of the first day at Headingley, when Australia were 203-3, Brearley opined that a side could be bowled out for 90 on that surface, and it may well have been the case had Australia gone in again that something along those lines happened – third innings collapses are not unknown by any means (Australia once lost a test match after not enforcing when they were rolled for 99 in the third innings and South Africa successfully chased over 300, and Essex in 1904 and Warwickshire in 1982 to name but two can tell their own tales of horrendous third innings folds), and with a draw out of the question England may well have chased a target of just over 300. In the ‘timeless match’ that marked the end of Sandham’s test career England skipper Calthorpe declined to enforce the follow on, and the West Indies were 408-5 (Headley 223) chasing 836 when rain and England’s departure plans scuppered the match. Six years earlier Calthorpe had been involved in a credulity straining comeback, when Hampshire collapsed for 15 in their first innings, Calthorpe enforced the follow on and Hampshire made 521 second time round and emerged victorious by 155 runs. However, we have the word of Warwickshire keeper Tiger Smith that autocratic secretary RV Ryder had sent Calthorpe a message saying that the committee were meeting the following day and would like to see some cricket, and Calthorpe obediently put on some part time bowlers to ensure that there was not an early finish. In other words, this was another match in which the decision to enforce was not itself key to the outcome. Finally, we come to the last ever timeless test, at Durban in early 1939. South Africa batted first, made 530, England were out for 316, South Africa, scorning to enforce the follow on, scored a further 481, leaving England 696 to get. England, helped by a long defensive innings from Paul Gibb (140 in nine hours) and a double century from Bill Edrich (who had never previously scored a test 50) had reached 654-5, a mere 42 short of their goal, when rain and England’s departure plans intervened, and 11 days after its commencement the match was officially confirmed as a draw. Had the match, as originally intended, been played to its conclusion, there seems little doubt that England would have scored those last 42 runs, and claimed the victory. One man who was utterly convinced that South Africa’s failure to enforce the follow on was a blunder was England skipper Hammond, who was no fan of timeless matches (and for the record, neither am I). Hammond felt that after that 316 all out in their first innings England were demoralized, and that a follow on would have seen South Africa comfortably home.

My opinion on enforcing the follow on is that there are a few circumstances in which I might countenance not enforcing it, to whit:

- It is the last (five day) test of a series, and your side is a match to the good. While I would consider it stolid, if not downright negative, I would understand the reasoning behind declining to enforce and aiming instead to pile up a colossal lead.

- It is the final round of the County Championship, and your team, at the top of the table, are playing the team in second place, and a draw will see you champions, while a defeat would see the opposition take the title. Again, while I would not go so far as to support a decision to to enforce, I would understand the reasoning behind it.

- Notwithstanding a couple of counter examples already mentioned, in a timeless match I could understand why it might seem imperative to rest your bowlers by going in again.

However, even making due allowance for these specific situations, my firm opinion remains: if you have the opportunity to go for the quick kill by enforcing the follow on you should be very strongly inclined to take it.

PHOTOGRAPHS

Another ‘All Time XI’ has paraded its skills on this blog, a couple of magnificent cricketers have been given well merited honourable mentions and an answer has been offered to the question of whether or not to enforce the follow, and all that remains is my usual sign off…