A piece principally about Ashes moments at the Oval cricket ground, with an introductory mention of the history of the two stations that serve it.

INTRODUCTION

Welcome to the latest post in my series “London Station by Station”. I hope you will enjoy this post and that some of you will be encouraged to share it.

IN THE SHADOW OF THE GAS HOLDERS

I am treating these two stations together because they are at opposite ends of the Oval cricket ground. Oval was one of the original six stations of the City and South London Railway, the world’s first deep-level tube railway, which opened in 1890. Vauxhall only opened as an underground station in 1971, part of the newest section of the Victoria line, but is also a main-line railway station and would have opened in that capacity long before Oval.

Today is the Saturday of the Oval test, by tradition the last of the summer. At the moment things are not looking rosy for England, but more spectacular turnarounds have been achieved (bowled at for 15 in 1st dig and won by 155 runs a day and a half later – Hampshire v Warwickshire 1922, 523-4D in 1st dig and beaten by ten wickets two days later – Warwickshire v Lancashire 1982 to give but two examples). The Oval in it’s long and illustrious history has seen some of test cricket’s greatest moments:

1880: 1st test match on English soil – England won by five wickets, Billy Murdoch of Australia won a sovereign from ‘W G’ by topping his 152 in the first innings by a single run.

1882: the original ‘Ashes’ match – the term came from a joke obituary penned after this game by Reginald Shirley Brooks. Australia won by 7 runs, England needing a mere 85 to secure the victory were mown down by Fred Spofforth for 77.

1886: A triumph for England, with W G Grace running up 170, at the time the highest test score by an England batsman. Immediately before the fall of the first England wicket the scoreboard nicely indicated the difference in approach between Grace and his opening partner William Scotton (Notts): Batsman no 1: 134 Batsman no 2: 34

1902: Jessop’s Match – England needing 263 in the final innings were 48-5 and in the last-chance saloon with the tables being mopped when Jessop arrived at the crease. He scored 104 in 77 minutes, and so inspired the remainder of the English batsmen, that with those two cool Yorkshiremen, Hirst and Rhodes together at the death England sneaked home by one wicket.

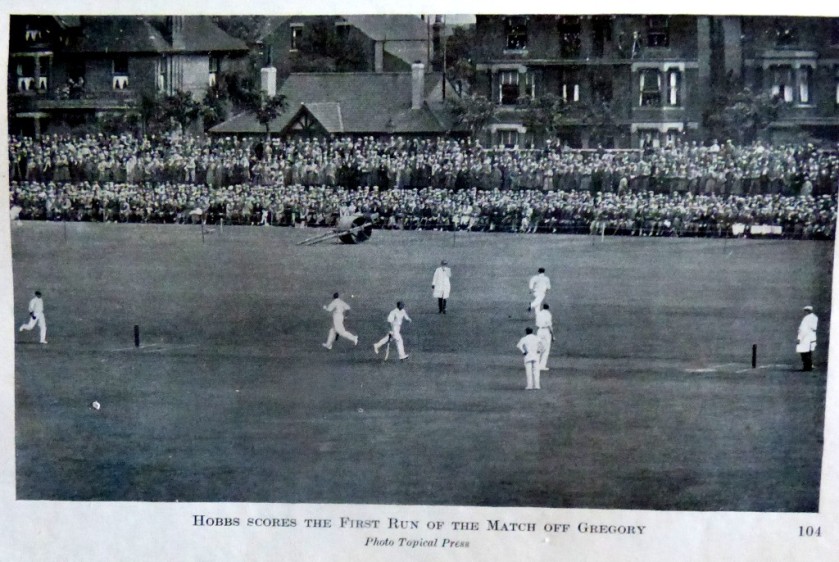

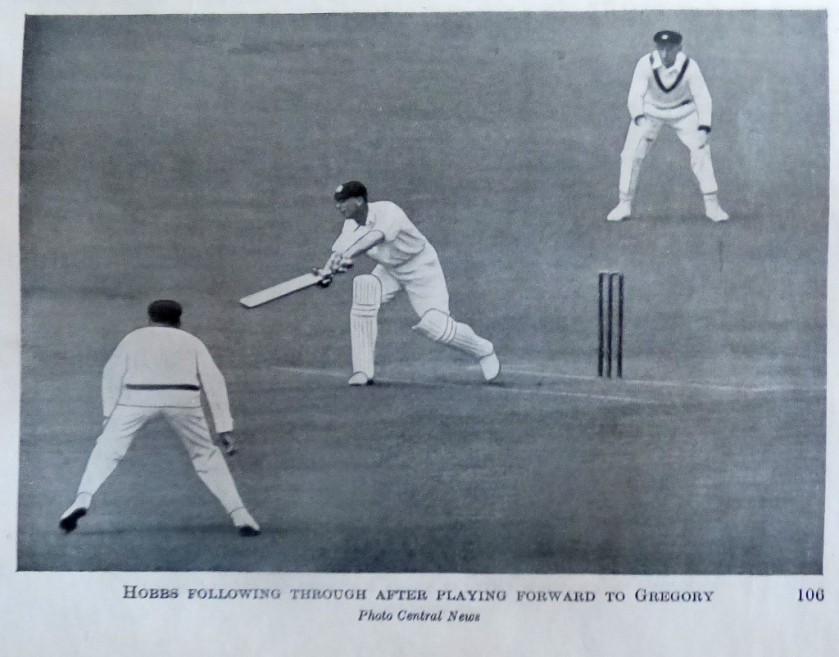

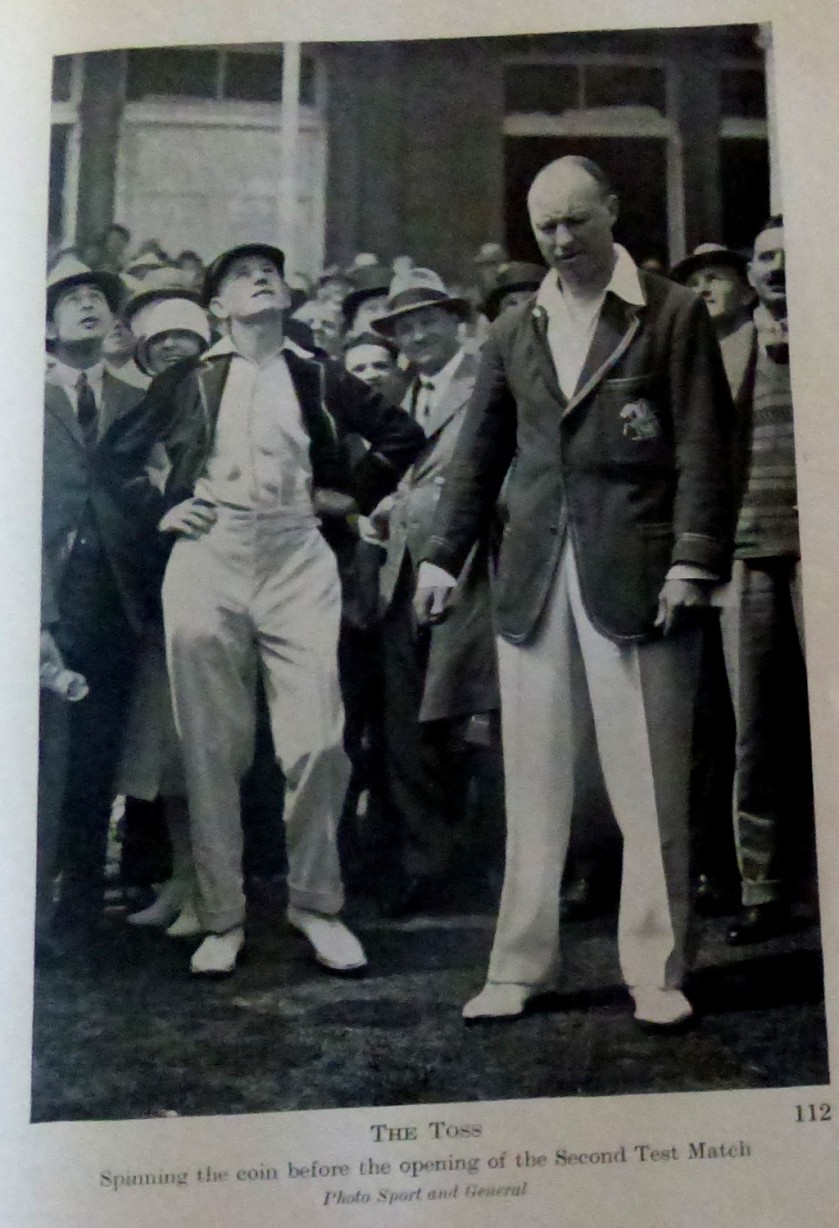

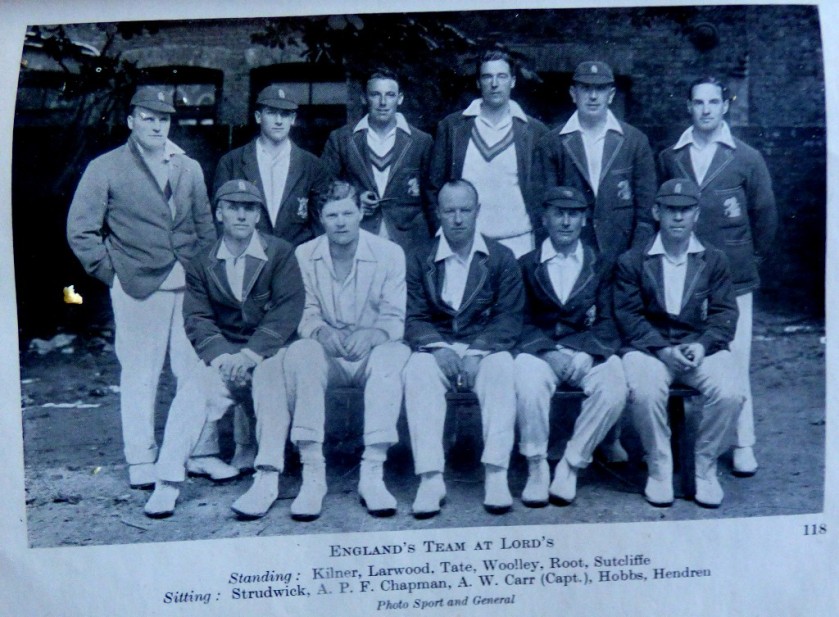

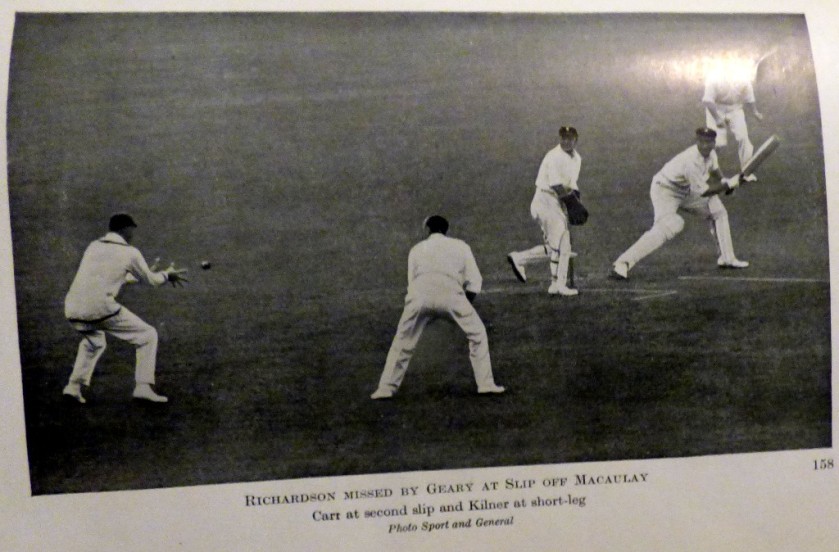

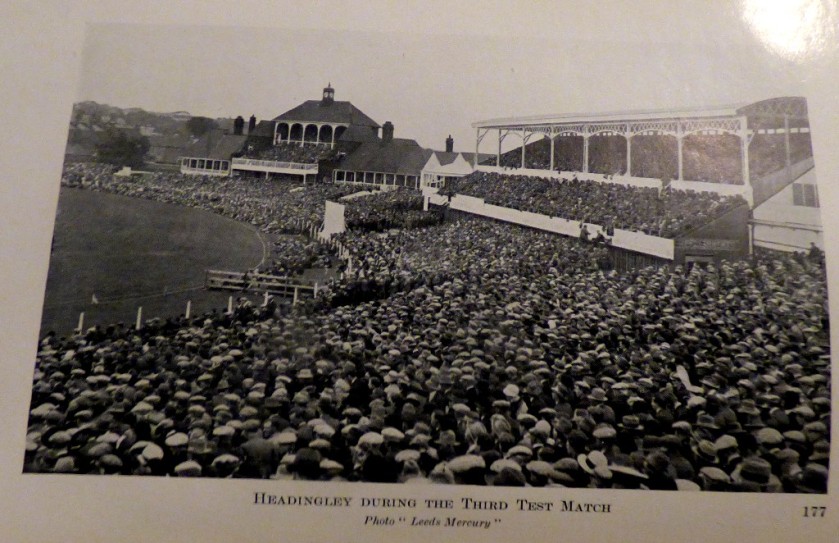

1926: England’s first post World ward I Ashes win, secured by the batting of Sutcliffe (161) and Hobbs (100) and the bowling of young firebrand Larwood and old sage Rhodes – yes the very same Rhodes who was there at the death 24 years earlier.

1938: The biggest margin of victory in test history – England win by an innings and 579. Australia batted without opener Jack Fingleton and even more crucially no 3 Don Bradman in either innings (it was only confirmation that the latter would not be batting that induced England skipper Hammond to declare at 903-7)

1948: Donald Bradman’s farewell to test cricket – a single boundary would have guaranteed him a three figure batting average, but he failed to pick Eric Hollies’ googly, collecting a second-ball duck and finishing wit a final average of 99.94 – still almost 40 runs an innings better than the next best.

1953: England reclaim the Ashes they lost in 1934 with Denis Compton making the winning hit.

1968: A South-African born batsman scores a crucial 158, and then when it looks like England might be baulked by the weather secures a crucial breakthrough with the ball, exposing the Australian tail to the combination of Derek Underwood and a rain affected pitch. This as not sufficient to earn Basil D’Oliveira an immediate place on that winter’s tour of his native land, and the subsequent behaviour of the South African government when he is named as a replacement for Tom Cartwright (offically injured, unoffically unwilling to tour South Africa) sets off a chain of events that will leave South Africa in the sporting wilderness for almost quarter of a century.

1975: Australia 532-9D, England 191 – England in the mire … but a fighting effort all the way down the line in the second innings, Bob Woolmer leading the way with 149 sees England make 538 in the second innings and Australia have to settle for the draw (enough for them to win the series 1-0).

1985: England need only a draw to retain the Ashes, and a second-wicket stand of 351 between Graham Gooch (196) and David Gower (157) gives them a position of dominance they never relinquish, although a collapse, so typical of England in the 1980s and 90s sees that high-water mark of 371-1 turn into 464 all out. Australia’s final surrender is tame indeed, all out for 241 and 129 to lose by an innings and 94, with only Greg Ritchie’s 1st innings 64 worthy of any credit.

2005: For the second time in Oval history an innings of 158 by a South-African born batsman will be crucial to the outcome of the match, and unlike in 1968, the series. This innings would see Kevin Peter Pietersen, considered by many at the start of this match as there for a good time rather than a long time, finish the series as its leading run scorer.

2009: A brilliant combined bowling effort from Stuart Broad and Graeme Swann sees Australia all out for 160 after being 72-0 in their first innings, a debut century from Jonathan Trott knocks a few more nails into the coffin, and four more wickets for Swann in the second innings, backed by the other bowlers and by Andrew Flintoff’s last great moment in test cricket – the unassisted run out of Ricky Ponting (not accompanied by the verbal fireworks of Trent Bridge 2005 on this occasion!).

The above was all written without consulting books, but for those who wish to know more about test cricket at this iconic venue, there is a book dedicated to that subject by David Mortimer.

As usual I conclude this post with some map pics…