Yesterday evening, overlapping with the end of the fourth test match (by then an inevitable draw, which I switched away from while keeping a cricinfo tab open), and also with most (but not quite all since it went to extra time and penalties) of the final of the Women’s European Championship between England and Spain, the final of the Women’s T20 Vitality Blast tournament took place between Surrey (league stage winners and as such automatic qualifiers for the final) and Warwickshire. After a brief wrap up of the test match this post will look back at that match.

A DRAW AND A POOR BIT OF THINKING/ BEHAVIOUR

By the time I changed radio channels away from the test match to the final of the Women’s T20 Blast tournament the draw was effectively signed, sealed and delivered, with the sole remaining question being whether either or both of Ravindra Jadeja and Washington Sundar would reach what I would consider to be well deserved centuries. Unfortunately Stokes, a great cricketer but not always the most sensible in other regards, failed to appreciate the niceties of this situation (Sundar especially deserved extra consideration as he had at this point not scored a test match century) and donning his “moral crusader’s cape” he offered India the draw as soon he was allowed to do so, ignoring the two milestones that were by then bulking large in the minds of the batters, and got grumpy when they did not accept his offer, preferring to bat on to secure their landmarks first and then accept the draw. The laws of this great game are unequivocal on the point that a draw can be accepted at any time in the last 15 overs of a match if both sides agree. Here, for obvious reasons, even though the draw had long been the summit of their ambitions, India were not ready to agree, and they could not be forced do. Stokes should have noted the scores of the two batters (especially Sundar), and waited until they either completed their tons or failed in the attempts. As to what actually eventuated I finish this section with two mastodon posts of mine, a few moments apart:

Post by @autisticphotographer@mas.to

and

Post by @autisticphotographer@mas.to

View on Mastodon

A TALE OF TWO SISTERS

The finals day for this competition featured a playoff in which Warwickshire faced The Blaze for the right to take on Surrey in the final and then the final itself. The first match was dominated by Issy Wong, who scored 59 and then took 4-14.

For the final Surrey won the toss and chose to bowl. Wong again batted well, but did not go really big this time, managing 31. That would remain the highest Warwickshire score of the innings. Laura Harris was typically explosive but only did half a job, going for 25 off 11 balls. It took some good work by the Warwickshire tail to get them past 150. They ended with 153-9, a good recovery from 115-8 at the dismissal of Harris, but a total that a powerful Surrey line up would have been confident of chasing.

The big difference between the two sides was that whereas Warwickshire had had lots of useful efforts but no big contribution Surrey got a clearly defined match winning innings from Grace Harris, sister of Laura (hence the title of this section of the post). Grace did not score quite as explosively as Laura had, but she did rack up an unbeaten 63, the highest score of the day, and she still only took 33 balls to make that score. The real key to her innings was that she was always scoring – of the 25 balls she took to reach her 50 she actually scored off 24 and faced only one dot ball. With Dunkley and keeper Chathli (who had earlier been superb with the gloves) playing support roles (23 off 13 and 16 not out off 9 respectively) Surrey won by five wickets with 3.2 overs to spare, a victory every bit as comprehensive as the margin suggests. Most of Warwickshire’s bowlers did reasonably well, though Millie Taylor, the young wrist spinner who was the tournament’s leading wicket taker came badly unstuck in the final, finishing with 3-0-37-0. The much more experienced Georgia Davis leaked 14 from her only over. Issy Wong was relative economical (under eight an over), but would have been disappointed to finish wicketless. It was Chathli who made the winning hit, a drive down the ground off Wong. Grace Harris, having produced score over twice the size of anyone else in the match, was named Player of the Match. Full scorecard here.

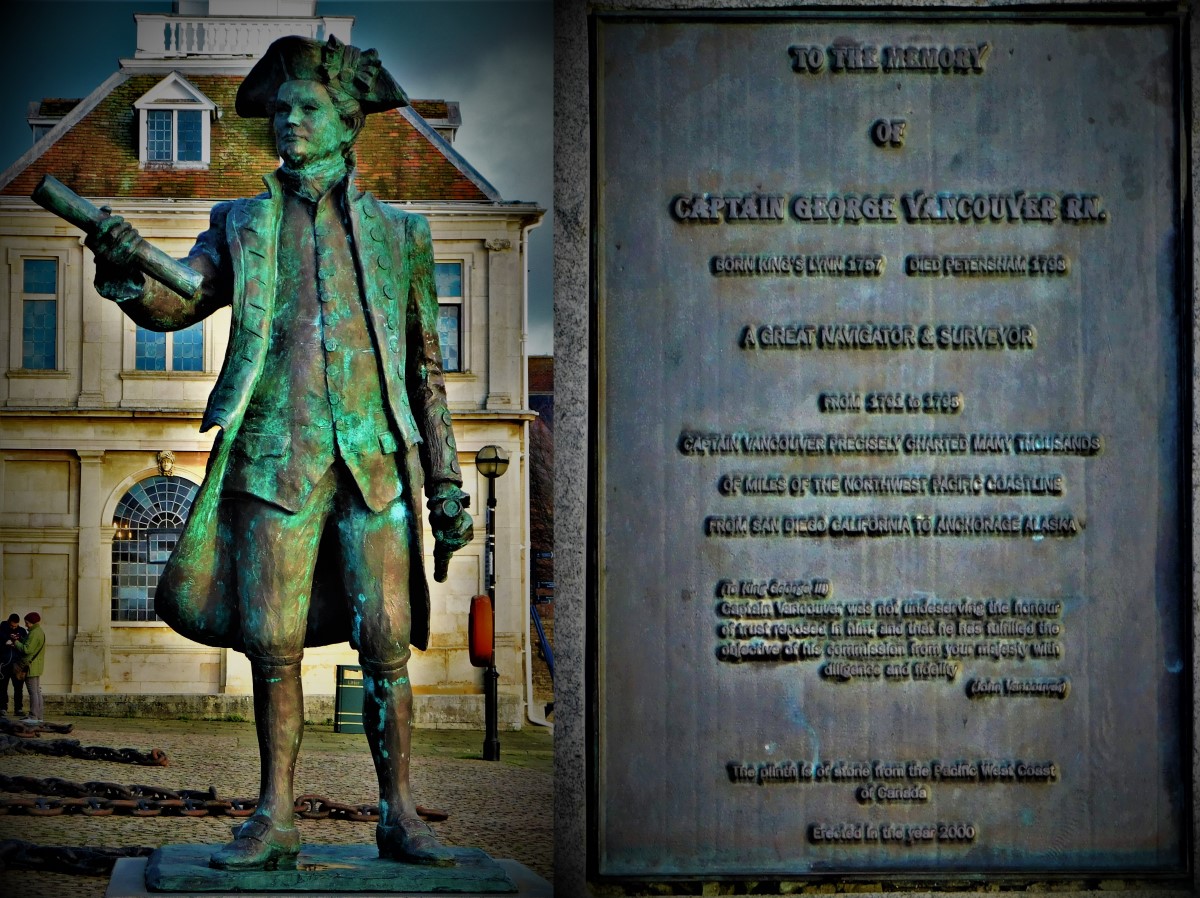

PHOTOGRAPHS

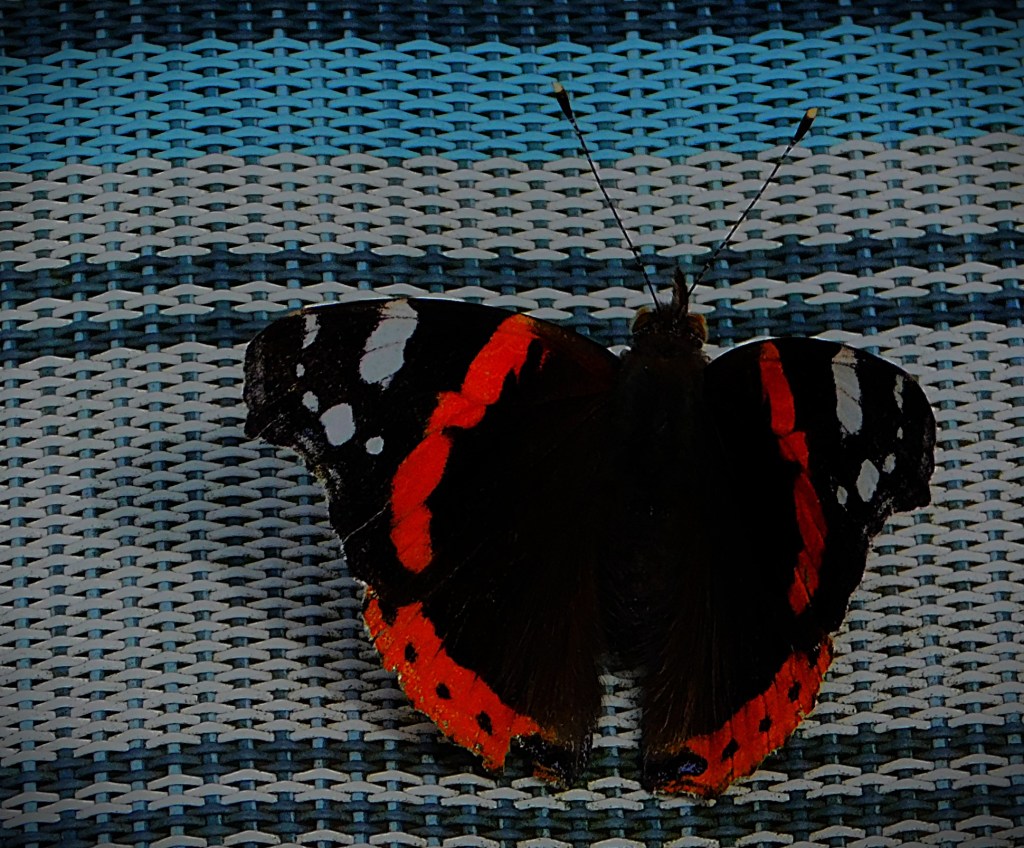

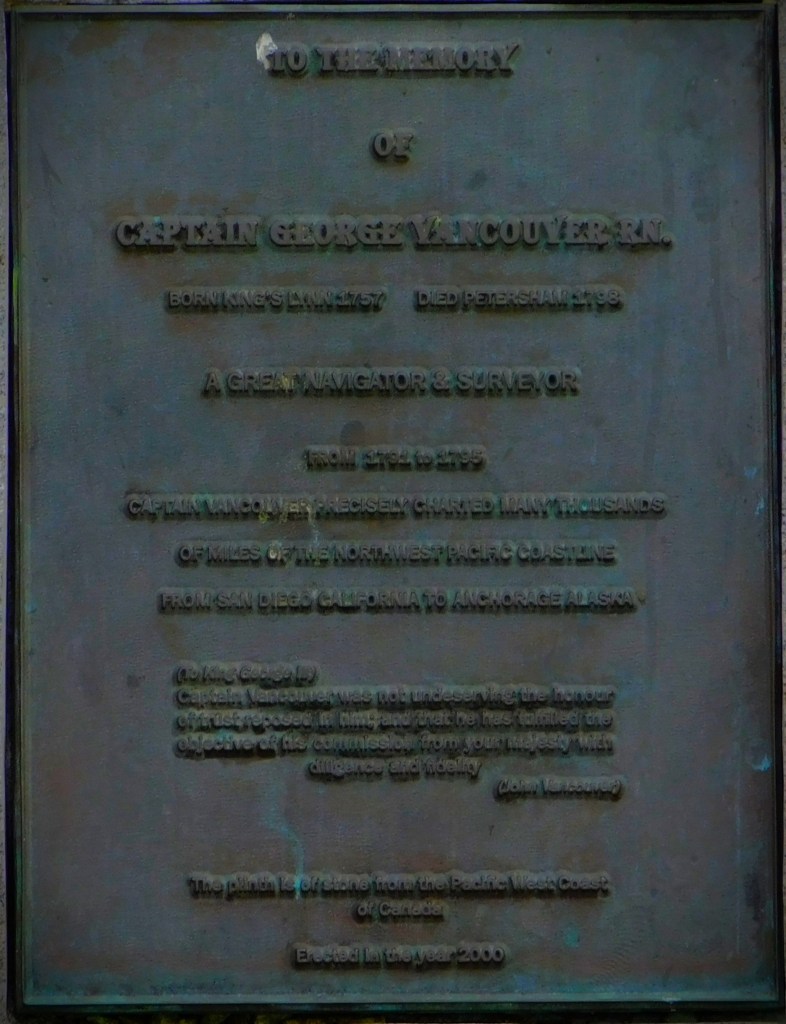

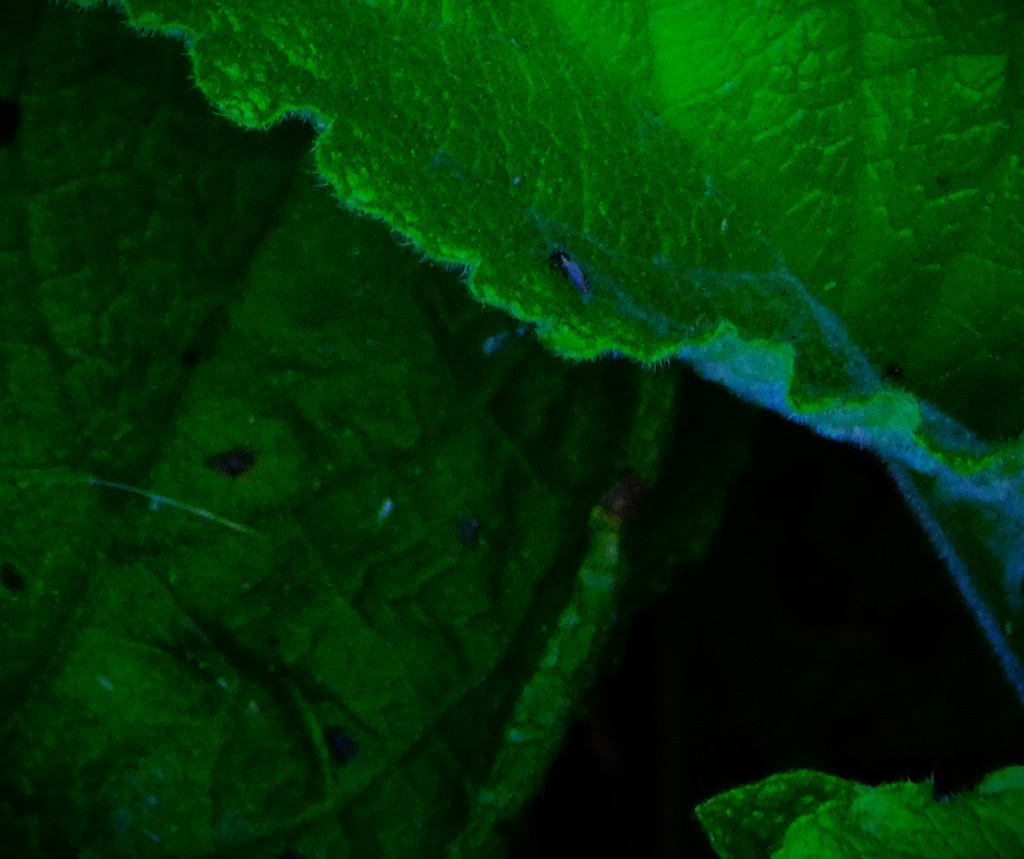

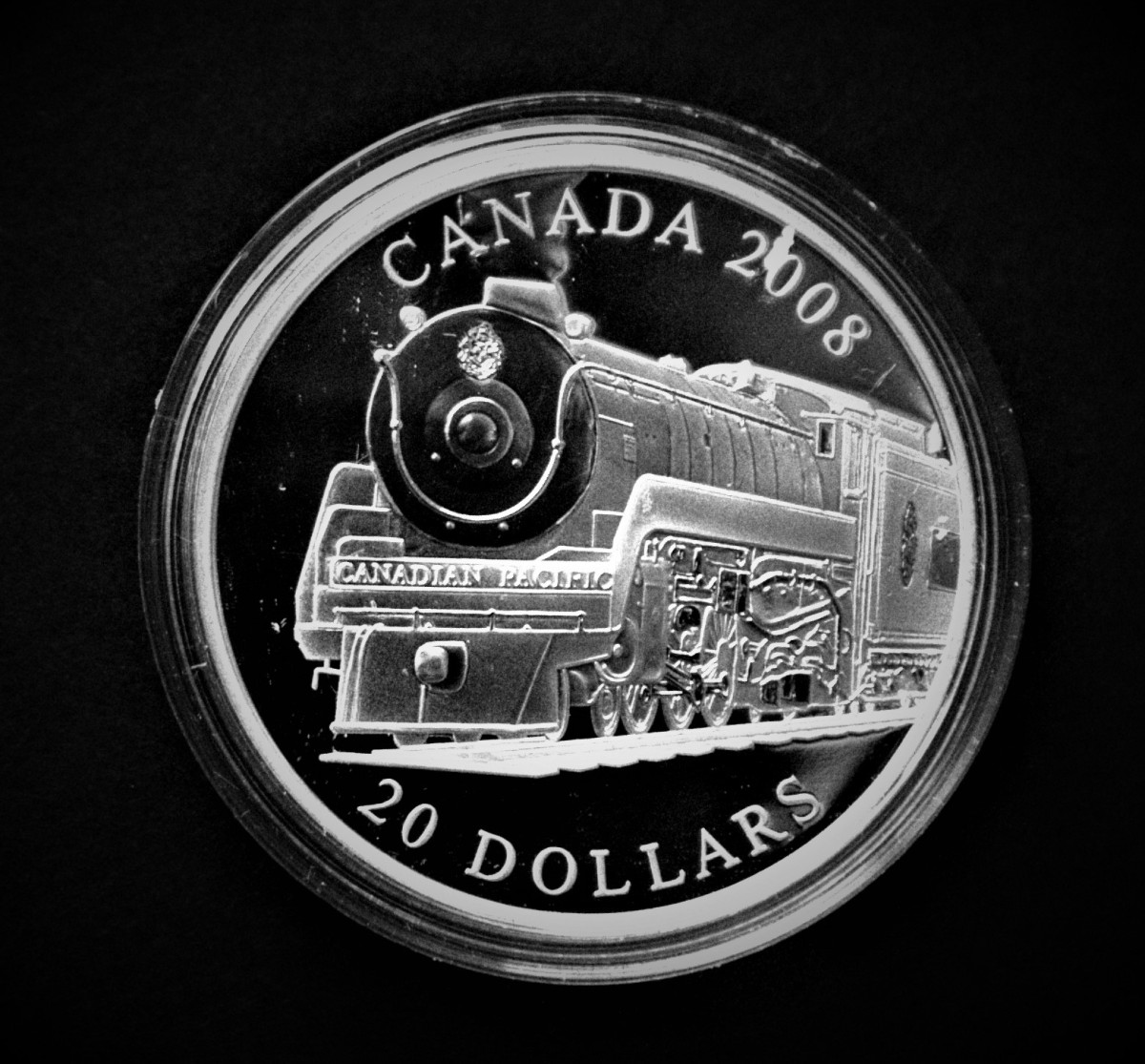

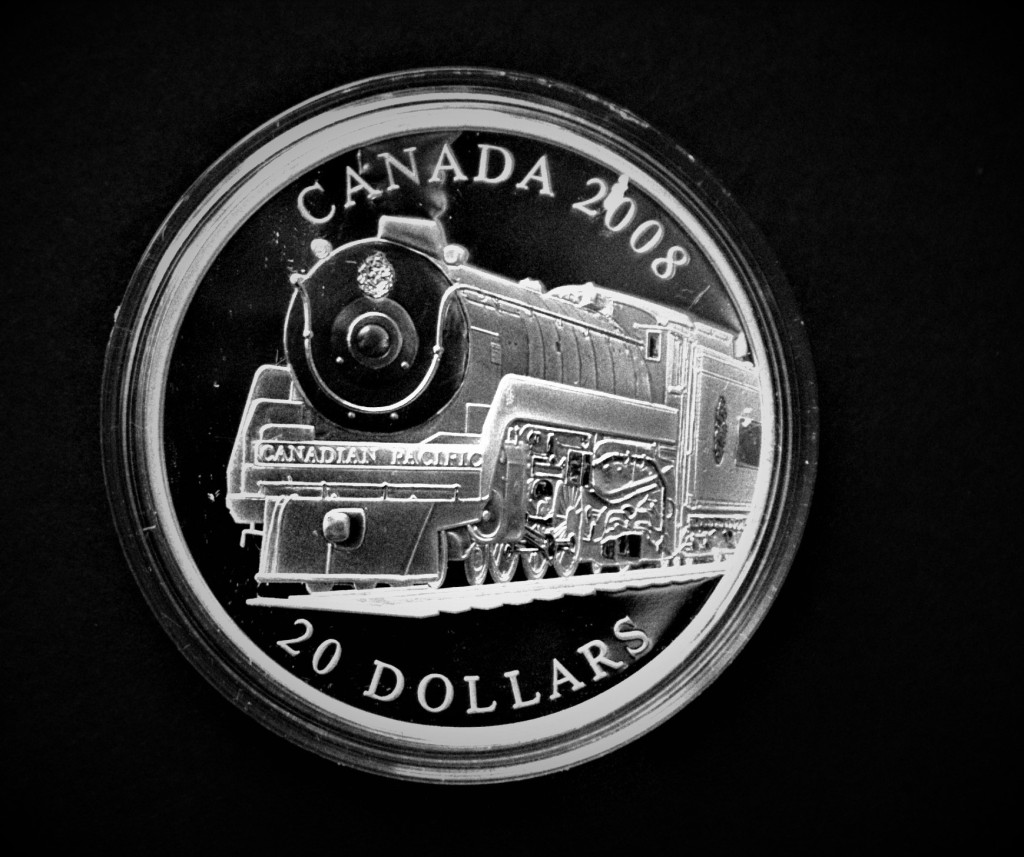

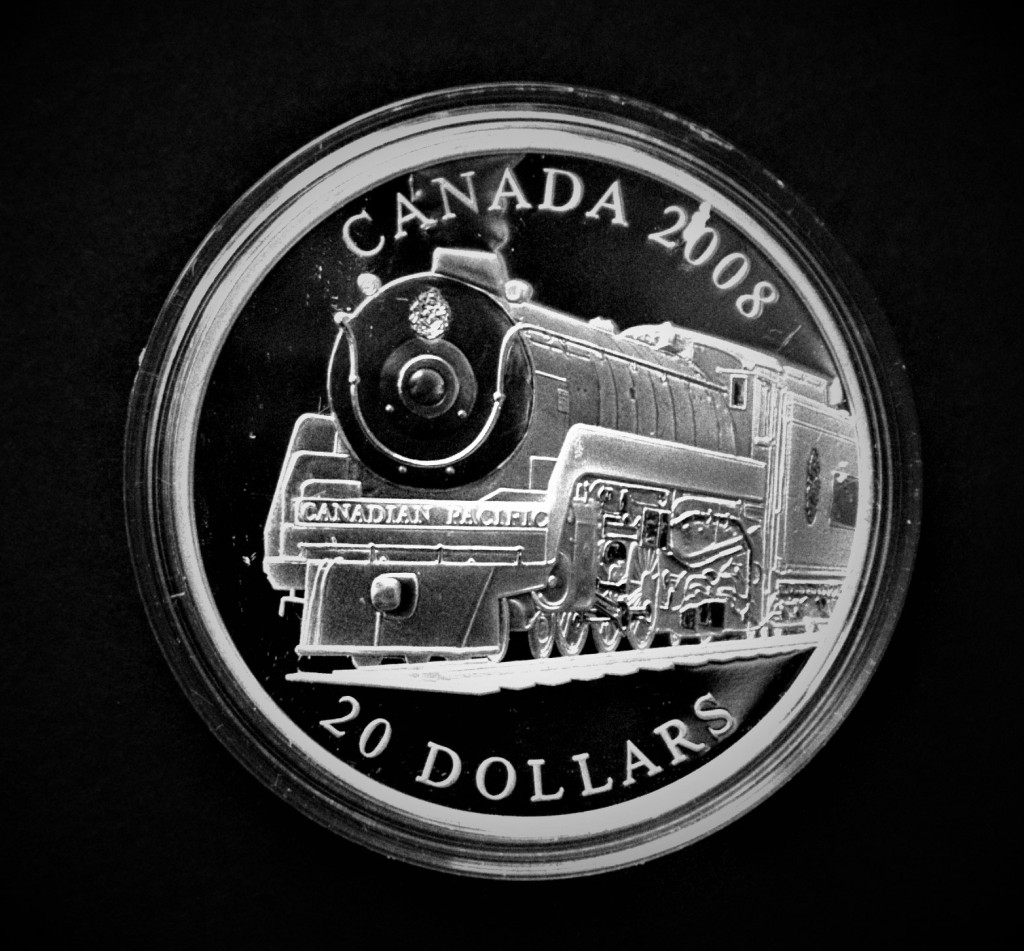

My usual sign off…(periodic reminder, to view an image at larger size simply click on it, and if you do this for the first image in a gallery you can view the whole gallery as a slide show).