INTRODUCTION

This post looks back at the test match that concluded yesterday evening in Manchester and forward to the one that starts at the same ground on Friday morning.

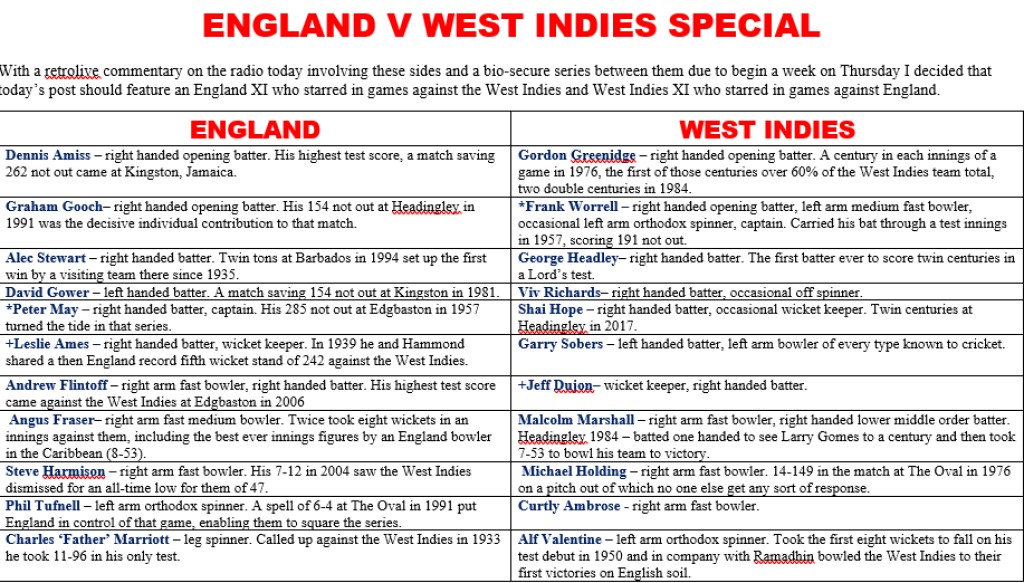

THE TALE OF THE TAPE

Thursday morning at Old Trafford was grey and rainy, and so play got underway late. England were deprived of Archer due to that player’s misconduct in between the Ageas Bowl and Old Trafford, had already decided to rest Wood and Anderson, while Crawley was correctly retained with Joe Denly losing his place, presumably permanently. Thus England’s line up read: Sibley, Burns, Crawley, *Root, Stokes, Pope, +Buttler, Woakes, Curran, Bess, Broad. This was a very strong batting line up, but there was no genuine pace in the bowling attack, with the possible exception of Stokes. The West Indies were unchanged.

Jason Holder won the toss for the West Indies and immediately made the first mistake of the match when he allowed himself to be influenced by the overhead conditions and chose to bowl first on a very flat looking pitch. At first things did not look too bad for the West Indies as Burns and Crawley fell cheaply, and even when Root was third out the score had only reached 81. At this point Ben Stokes got into the action, and was scarcely to be out of ti again for the rest of the match. Sibley was looking secure at one end, and now Stokes displayed considerable resolve and patience to stay with him. By the end of the first day the fourth wicket pair were still in occupation and the score was 207-3, and the decision to bowl first stood revealed as a ghastly howler on Holder’s part. On the second day Stokes and Sibley consolidated their position, with Sibley reaching his second test century just before lunch, and Stokes completing his tenth such score just afterwards. Finally, with the score at 341 Sibley fell for 120, having also completed a century of a much rarer kind – 100 balls left alone in the course of a single innings. GThe stand of 260 was the second highest ever for any wicket at Old Trafford, though some way short of England’s all time fourth wicket record stand, the 411 put on by Peter May and Colin Cowdrey versus the West Indies at Edgbaston in 1957. Pope fell cheaply, bringing Buttler to the crease at 352-5, and with an opportunity, undeserved in many opnions including mine, to cash in on tired bowlers. Ben Stokes was finally dislodged for 176, his second highest test score, with the score at 395, Woakes fell first ball which brought Curran to the crease. At 426 Buttler who had made a less than impressive (given the ultra favourable circumstances) 40 was caught off the bowling of Holder. One run later Curran was out. Dom Bess, in company with Stuart Broad, played a useful cameo reaching 31 not out before Root declared with the score at 469-9. John Campbell was out in the mini-session of batting the West Indies had before day 2 closed, Alzarri Joseph was sent in as nightwatchman and took them through to the close, at which point they were 32-1. Day three was washed out, a big dent to England’s hopes. In the middle of the fourth afternoon the West Indies were 235-4 and the draw was a strong favourite. Then that man Stokes intervened again, bowling a hostile spell in which he accounted for the obdurate Kraigg Brathwaite and destabilized the West Indies innings. Stuart Broad then bowled a magnificent spell with the second new ball before Woakes took a couple of late wickets, and the West Indies were all out for 287, giving England a lead of 182. With quick runs needed England sent in Buttler and Stokes. Buttler proceeded to be bowled for a third-ball duck, a dismissal which really should end his test career (he is a magnificent limited overs player but has never been anything special in long form cricket), which brought Zak Crawley to the wicket. Crawley made 11 before he too fell, and England closed the 4th day on 37-2, with Stokes and Root in occupation. England, as they had to in the circumstances, needing a win to keep both the Wisden trophy and their slender hopes of the World Test Championship alive, went on the all out attack on the final morning, blazing 91 off 11 overs before declaring at 129-3, with Stokes 78 not out and Pope 12 not out off seven balls. This left the West Indies needing 312 to win and with 85 overs to get them.

Broad bowled superbly with the new ball, and the West Indies rapidly plunged to 37-4. Blackwood and Brooks then put on exactly 100 together before that man Stokes broke the partnership, dismissing Blackwood for 55. Woakes then cleaned up Dowrich for a duck, bringing skipper Holder in to join Brooks. Holder and Brooks took the score to 161 before Curran pinned Brooks LBW, which went to review where it came up as umpires call, the third time a West Indian had suffered that fate in the innings. Holder and Roach offered some resistance before Bess made the crucial breakthrough, bowling Holder for 35, to make at 183-8, and leave three tailenders tasked with holding out for more than 20 overs to save the game. Alzarri Joseph scored nine, was then caught by Bess of the bowling of Stokes to make it 192-9. I had an evening engagement and was not able to catch the fall of the final wicket, that of Kemar Roach, caught by Pope off the bowling of Bess. England took that wicket just after umpire Richard Illingworth had signalled the start of the last 15 overs of the game and had won by 113 runs, meaning that the third match of this series will be a ‘winner takes all’ battle.

STOKES THE COLOSSUS

Stokes’ performance in this match saw him displace Jason Holder at the top of the test match all rounders rankings, and it also saw him rise to no3 in the world batting rankings behind Virat Kohli and ‘sandpaper’ Steve Smith. Stokes’ participation in this match was as follows: 176 off 356 balls spread over 487 minutes at the crease in the first innings, 1-29 off 13 overs in the second, with that wicket coming in the spell that destabilized the West Indies innings, 78 not out off 57 balls to set up the declaration in the third innings and 14.4 overs for figures of 2-30 (he was unable to complete his final over, the last two balls of it being bowled by Joe Root). At Lord’s in 1952 Mulvantrai Himmatlal ‘Vinoo’ Mankad scored 72 in the first innings, bowled a marathon stint of 73 overs in the England reply, scored 184 in the third innings and bowled a further 24 overs in the second England innings, this all round effort all coming to nought as his side were beaten anyway. In first class cricket there are George Hirst’s spectacular dominance over Somerset in 1906 – 111, 117 not out, six first innings wicket and five second innings wickets, George Giffen’s 271 not out, 7-70 and 9-98 for South Australia versus Victoria, while in 1874 WG Grace had a spell of sustained brilliance in which he combined centuries with ten wicket match hauls five times in the space of six matches. At club level there is the feat of Dr M E Pavri, an Indian all rounder who apparently bowled at a lively pace (he toured England in the 1880s, long before his country were promoted to test status, and there is a story of him sending a stump nine yards backwards in a match at Norwich), and who decided on one occasion that teammates were unnecessary, taking on an XI all on his own. In that game he batted first, scored 52 not out before deciding that he had enough runs to serve his purposes, and then without fielders to aid him dismissed the opposing XI for 38 to win the match.

ENGLAND PLAYER RATINGS

- Dom Sibley – 9 – a magnificent display of concentration in his only innings, though he was reprieved when Jason Holder dropped a fairly regulation chance, so it was not an absolutely blemish free effort.

- Rory Burns – 3 – a failure with the bat, nothing notably good or bad in the field.

- Zak Crawley – 4 – a first baller in the first innings, and also failed in the second innings thrash for runs, managing 11 off 15 balls, which does at least represent a half decent scoring rate.

- *Joe Root – 6 – two scores in the twenties, though in the second innings he was good foil to Stokes while the latter was lashing out. He was possibly a little conservative in the matter of the second innings declaration, but overall he captained well.

- Ben Stokes – 10 – he batted England into a commanding position with his first innings effort, his bowling intervention in the first West Indies innings was crucial in reopening the possibility of an England win, his second innings batting effort in altogether different circumstances was precisely what the team needed, and he again made the crucial breakthrough in the final innings when he broke the Brooks/Blackwood partnership. I reckon even Craig Revel-Horwood would have rated this performance a 10.

- Ollie Pope – 5 – failed in the first innings, 12 not out off 7 balls in the second to help England to the declaration and he performed the last action of the game, taking the catch that dismissed Kemar Roach.

- +Jos Buttler – 3 – his first innings 40 was unimpressive given the circumstances, he responded to being given the opportunity to open the innings and bat in his best T20 fashion with a third ball duck, and although he held on to three catches in the match this must be the end of the road for Buttler the test cricketer.

- Chris Woakes – 6.5 – failed with the bat in his only innings, but bowled well in both innings, reminding everyone that he is always difficult to play in English conditions.

- Sam Curran – 6 – only 17 with the bat, but bowled quite well. It was with his dismissal of Brooks in the second innings to make it 161-7 that moved victory from possible to probable.

- Dom Bess – 6.5 – his 31 not out in the first innings was a useful knock, he was economical though not penetrative in the first West Indies innings, and it was his delivery to bowl Jason Holder that effectively sealed the destiny of this match, while he completed a trio of late interventions by then catching Alzarri Joseph and finally picking up the wicket of Roach to complete the victory.

- Stuart Broad – 8.5 – he bowled a magnificent spell with the second new ball in the West Indies first innings to ensure that England would have a substantial advantage and bowled another fine spell with the new ball in the West Indies second innings which left them in tatters at 37-4.

LOOKING FORWARD TO FRIDAY

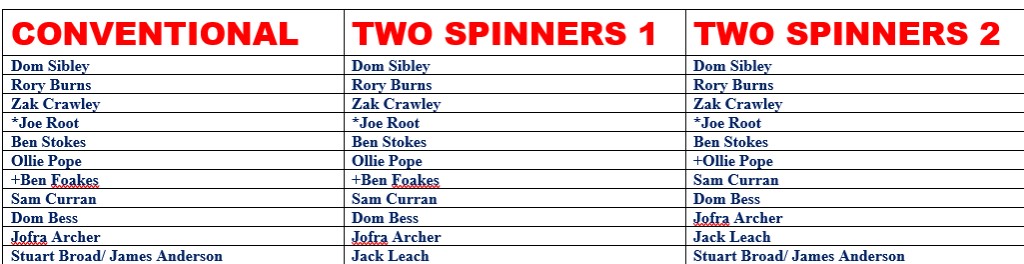

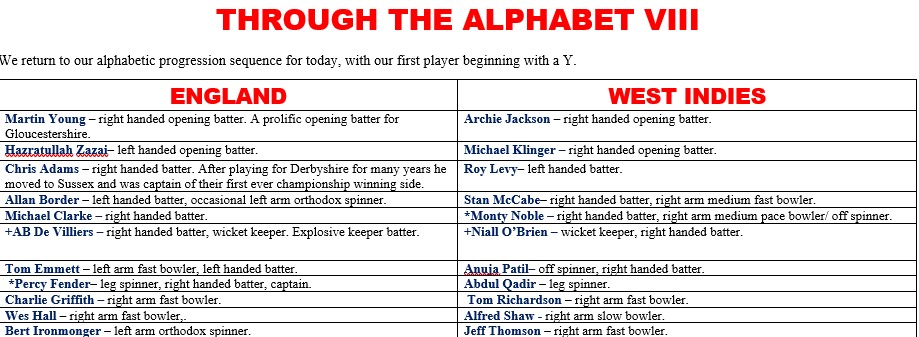

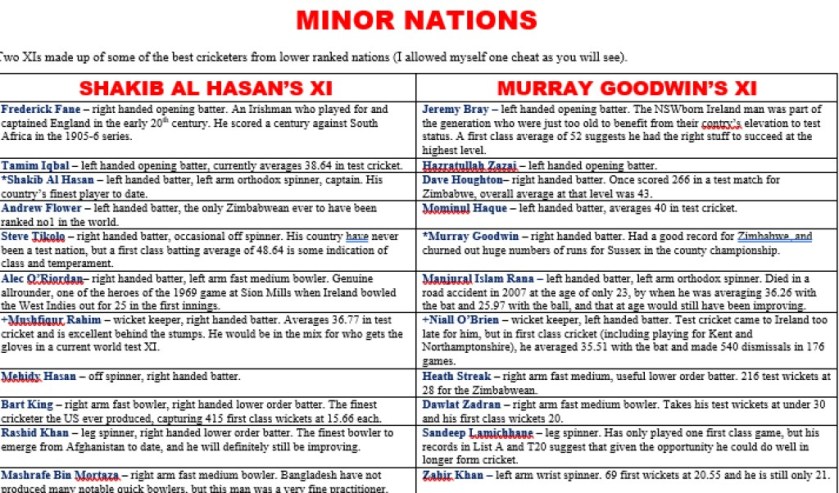

It is possible that England will want to play two spinners in the decider, and they could also maintain their rotation policy with Broad and Anderson, although I suspect that even in King’s Lynn I will not need the assistance of a radio to hear Mr Broad’s response should be told that he is being rested for the decider, and there is also the question of whether to play Archer in the decider. Of the three specialist batters who failed in this match two, Burns and Pope already have test hundreds, and it seems likely that the third, Crawley, will be joining them sooner rather than later, so I am not unduly worried about them. Buttler, just to re-emphasize the point has to go. Thus I offer up three potential line ups, two of which have permutations:

The first line up brings in Archer for his extra pace but sticks to one spinner and a choice between Broad and Anderson. The second line up accommodates two spinners but runs the risk of having Stokes as third seamer. The third line up is gamblers line up, entails Pope as keeper, a job he has done in test cricket, and five regular bowlers, with Stokes as back up. If England do decide to go with two spinners that would be my preferred option, although the second line up does at least have variety going for it – right arm fast (Archer), left arm medium fast (Curran), off spin and left arm orthodox spin plus x-factor Stokes. England need a win to regain the Wisden trophy and retain an interest in the World Test Championship, while the West Indies have not won a series in England since 1988, and so although a draw would see them retain the Wisden trophy it would not be a great result for them. So far this has been a splendid series, with England bouncing back well after the loss in Southampton.

TYING THINGS TOGETHER

The full scorecard for this fine match can be viewed here, courtesy of cricinfo. My other posts about this match are:

For a different view, here is the fulltoss blog’s account.

LINKS AND PHOTOGRAPHS

I have a varied trio of links to share today:

- First, from Gwent in south Wales, news of a pair of bitterns breeding, a first for 200 years in that part of the world, courtesy of birdguides,com.

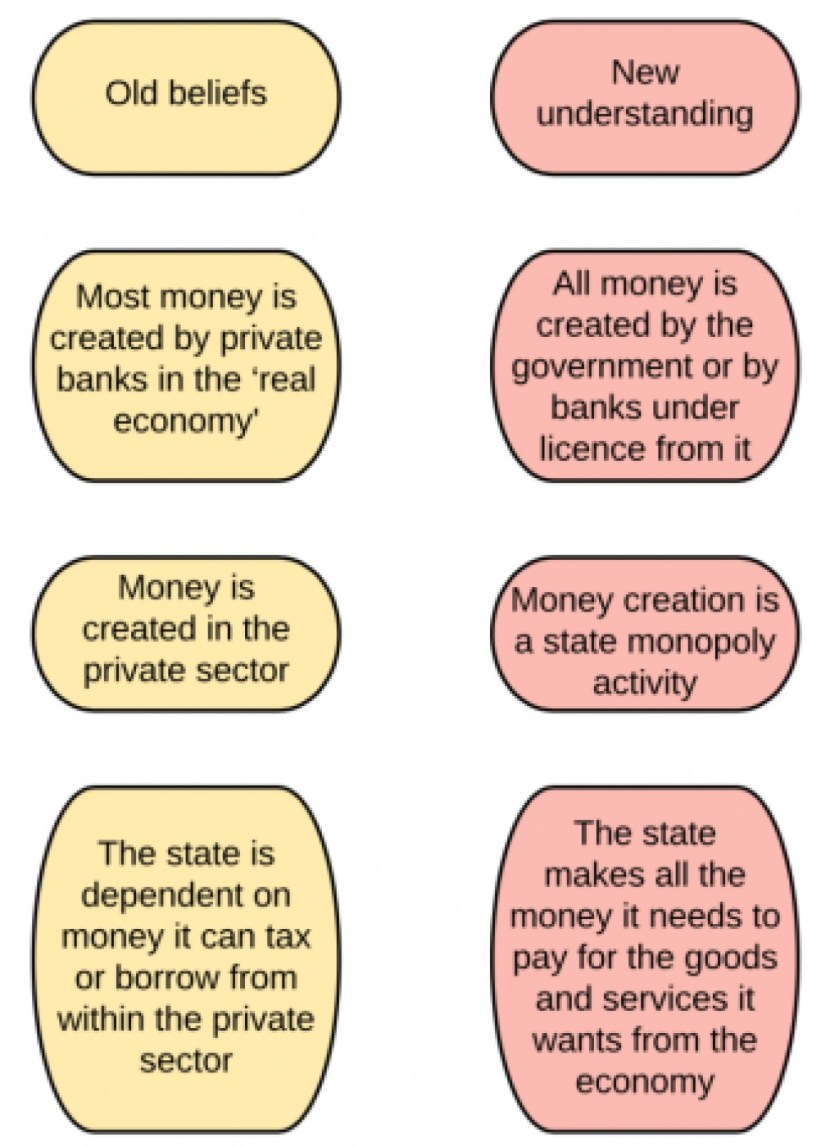

- Richard Murphy of Tax Research UK takes the FT to task for offering up an ‘economically incompetent view of tax‘.

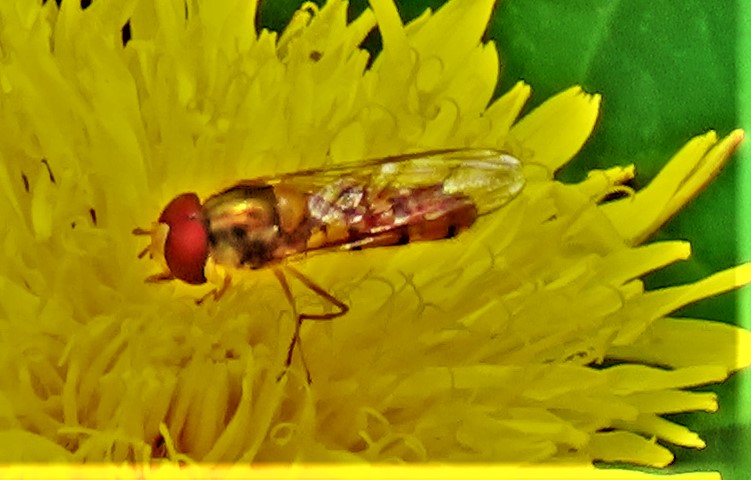

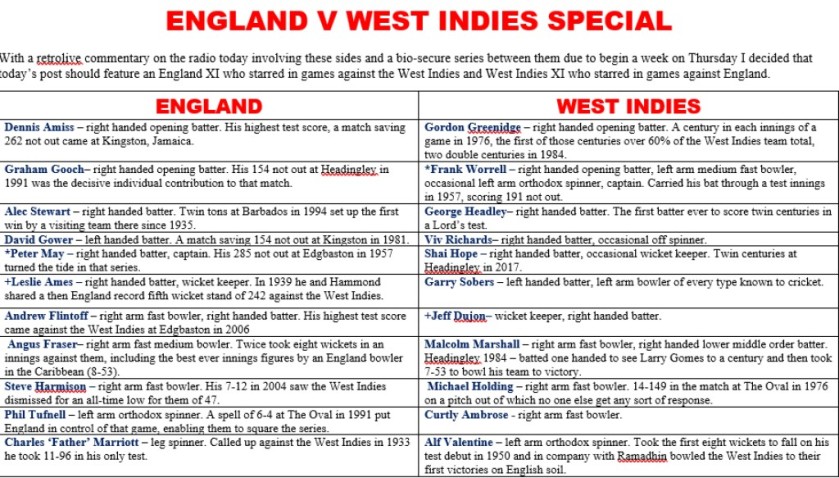

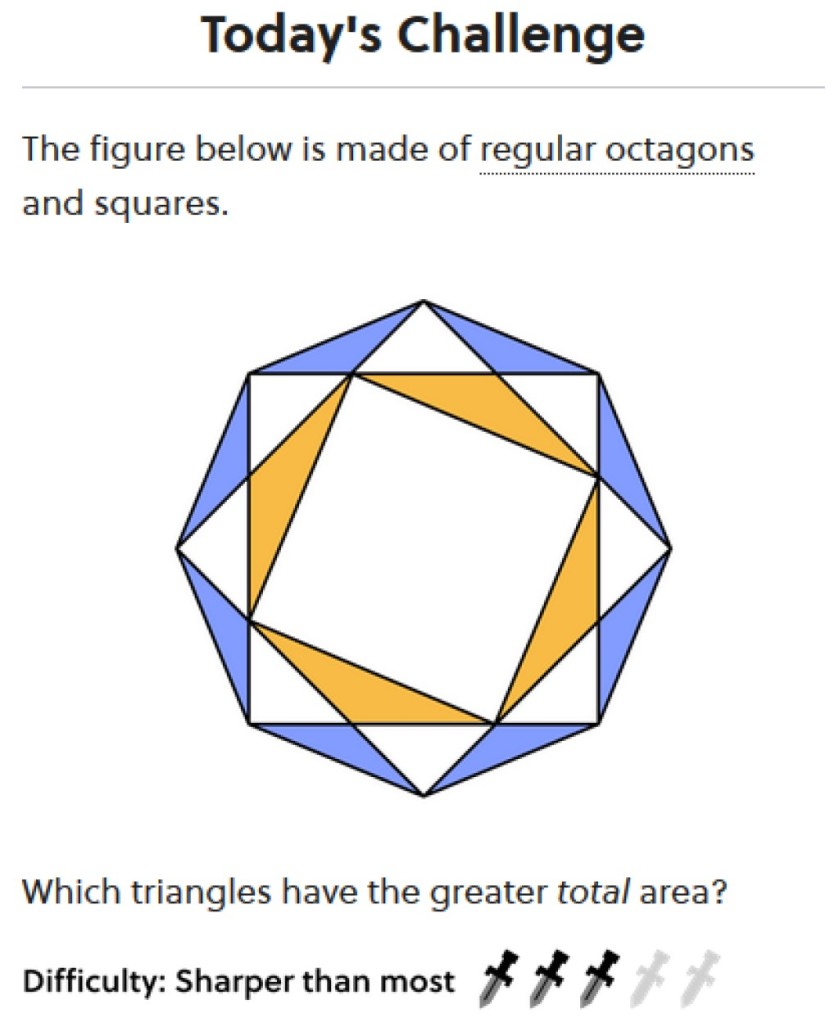

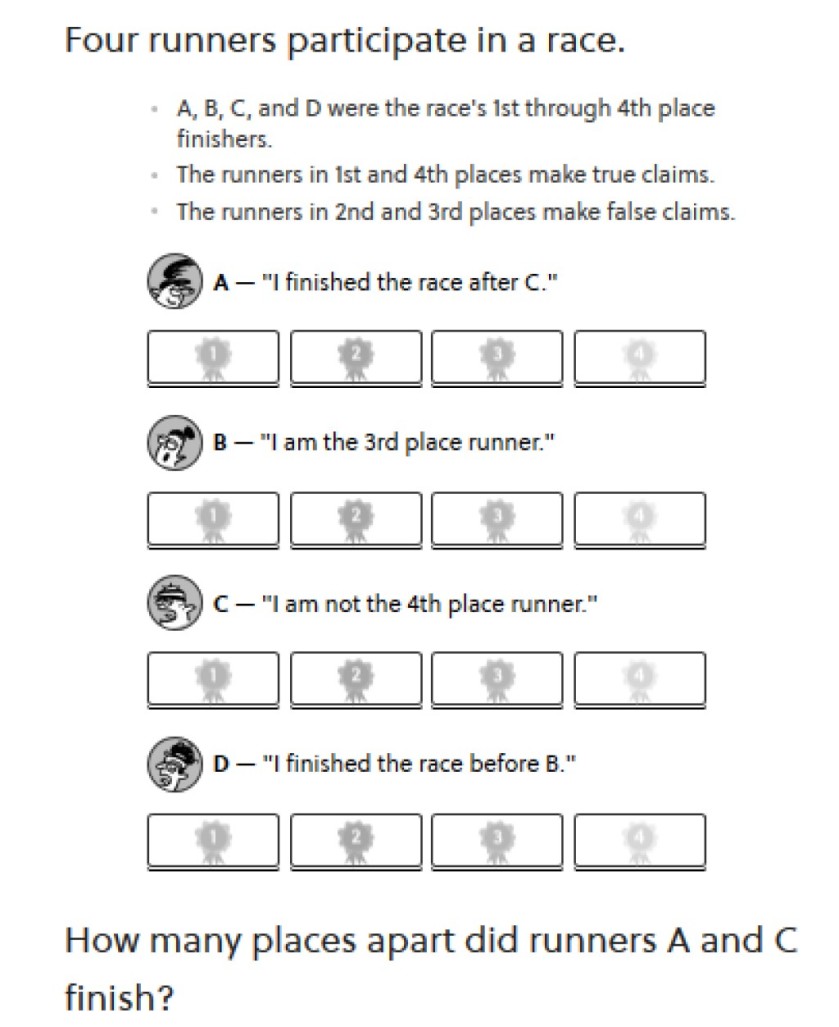

- Thirdly a teaser from brilliant, which is an absolute cinch if you spot how to solve it and basically impossible if you do not:

And now it is time for my usual sign off…