The new county championship season is only just over a month away, and of the 18 first class counties only two, Somerset and Northamptonshire have never won a county championship or been named Champion County (Gloucestershire have not won a championship since it was put on an organized footing in 1890, but were three times named Champion County in the 1870s). For this XI showcasing the talent that the two ‘Cinderella’ counties have produced I have deliberately avoided choosing any overseas players.

THE XI(I) IN BATTING ORDER

12 players are named here with the final choice dependent on conditions…

- Marcus Trescothick (Somerset, left handed opening batter, occasional right arm medium pacer). A stalwart of Somerset for many years, and a fine England career until mental health issues forced him to abandon international cricket.

- Colin Milburn (Northamptonshire, right handed opening batter). His career was ended early by a car accident which cost him his left eye, which for a right hand dominant player is the really important one (Mansur Ali Khan, the last Nawab of Pataudi, played on after the loss of an eye, but it was his right eye which is why he, also right hand dominant, was able to cope with the loss). He did enough before the accident to earn his place.

- David Steele (Northamptonshire, right handed batter, occasional left arm orthodox spinner). An adhesive number three who earned enduring fame as ‘the bank clerk who went to war’. when Tony Greig having sought opinions on which county players were hardest to dislodge had him called in to the England side in the 1975 Ashes and he responded with 365 runs in three test matches, which he followed up with another successful series against the West Indies with their first four pronged pace battery before being dropped for the tour of India due to suspicions about his ability to play spin on turning pitches.

- James Hildreth (Somerset, right handed batter, occasional right arm medium pacer). He never quite gained international recognition, but 18,000 first class runs at an average of 44 more than justify his inclusion here.

- Dennis Brookes (Northamptonshire, right handed batter). One of Northamptonshire’s finest middle order batters.

- Len Braund (Somerset, right handed batter, leg spinner). A genuine all rounder, one of three in this order including the captain, successful at international as well as county level.

- Vallance Jupp (Northamptonshire, right handed batter, off spinner). In the 1920s he achieved the double of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets in first class matches in each of eight successive seasons, a record of unbroken consistency in both departments beaten only by George Hirst of Yorkshire (1902-12 inclusive).

- *Sammy Woods (Somerset, right handed batter, right arm fast bowler, captain). Born in Sydney, but he settled in Somerset, and save for one series for England in South Africa which was only retrospectively granted test status he gave up test cricket having played a couple of matches for his native land. As a captain he was handicapped by Somerset’s heavy dependence on amateurs, which meant that the players at his disposal changed constantly, but still had his great moments, including leading the county to victories over Yorkshire, then the dominant force in county cricket, in each of three successive seasons.

- Frank Tyson (Northamptonshire, right arm fast bowler, right handed batter). One of the quickest ever – in the 1954-5 Ashes he joined Larwood in the club of England fast bowlers to have blitzed the Aussies in their own backyard, a club expanded when John Snow did likewise in 1970-1.

- +Wally Luckes (Somerset, wicket keeper, right handed batter). For a quarter of a century he was a stalwart of Somerset sides, noted in particular for leg side stumpings. His lowly position in the order was forced on him by medical advice that batting was not good for his health – his doctor only allowed him to keep playing if he agreed to bat low in the order. He once scored 121* from number five, but his usual role with the bat was helping Somerset to last gasp victories, like against Gloucestershire in 1938 when hit the third and fourth balls for the last possible over for fours to give his side a one wicket win.

- This is the position that has two possibilities:

a) Ted ‘Nobby’ Clark (Northamptoinshire, left arm fast bowler, left handed batter). In the 1930s he was probably as quick as anyone not named Larwood, and after the 1932-3 Ashes when England rewarded the bowling star of that series by making him persona non grata Clark did get to play for England, notably on the 1933-4 tour of India which was Jardine’s last international outing.

b)Jack ‘Farmer’ White (Somerset, left arm orthodox spinner, right handed batter). An excellent FC record (2,355 wickets at 18.58 including an all-ten), and he was a crucial part of England’s 4-1 win in the 1928-9 Ashes, when his unremitting accuracy and stamina meant that the faster bowlers had a bit of breathing space – at Adelaide he bowled 124 overs in the match, taking 13-256. If White were to get the nod Luckes would bat at 11, and Tyson would also drop a place in the order – White was a competent lower order batter, whereas Clark was not.

This side has a powerful top five, three genuine all rounders, a great keeper who would have batted higher in the order had his health permitted, and according to circumstances either two specialist quicks to back up Woods or Frank Tyson and a great left arm spinner. Neither possible attack – Tyson, Woods, Clark, Jupp and Braund, or Tyson, Woods, White, Jupp and Braund – would be likely to struggle to take 20 wickets.

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

Harold Gimblett (Somerset, right handed opening batter) is designated as reserve opener, and I would not argue with anyone who picked him in the XI. Woods’ slot might have gone to Ian Botham or Arthur Wellard, though the former would have made the side more batting dominant than I would like. I wanted Woods’ captaincy which is what settled it for him. Both counties have had decent spinners over the years, but I wanted the all round skills of Braund and Jupp, and considered White a cut above the other specialist spinners.

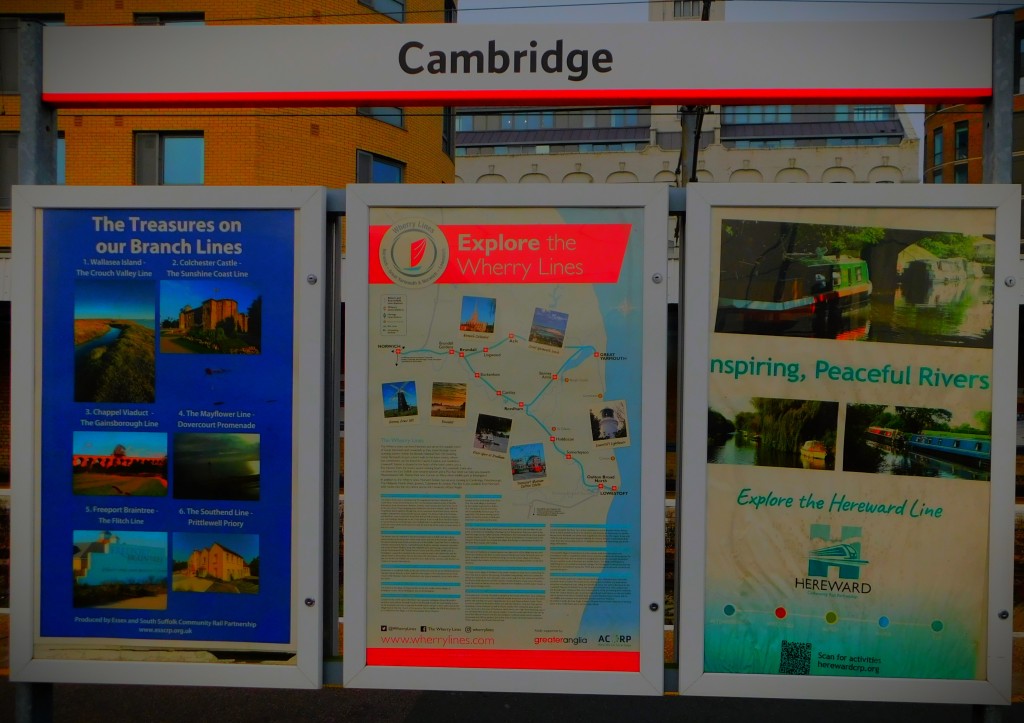

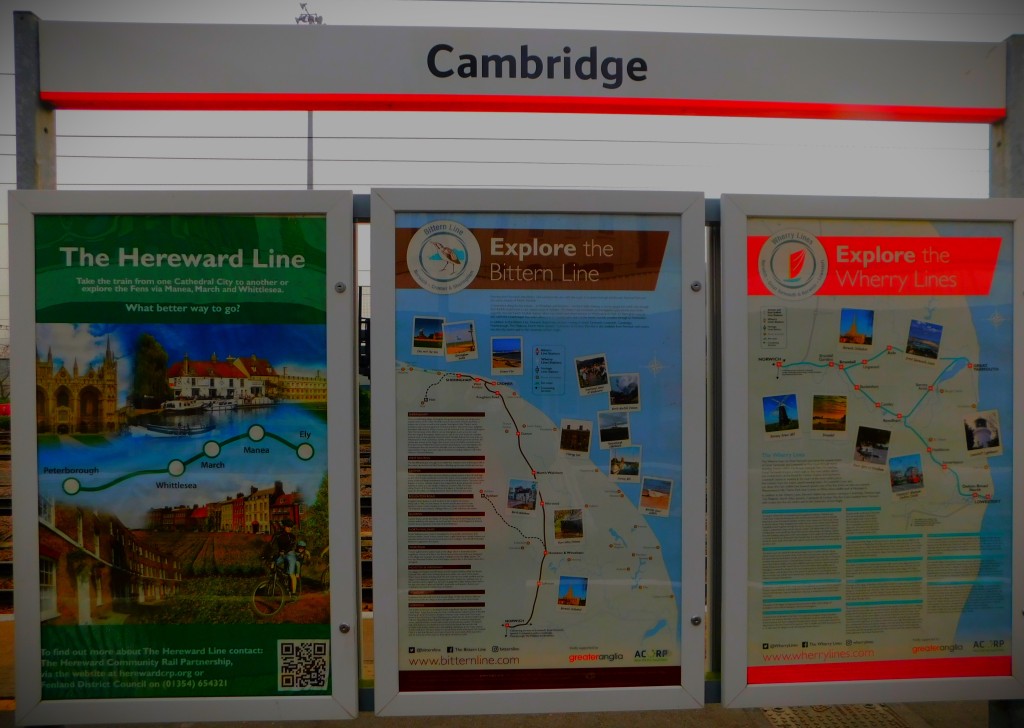

PHOTOGRAPHS

My usual sign off…