Declarations have been in the cricket news again lately after one by Australian captain Pat Cummins didn’t work out for him. In this post I look at that declaration and some stories from cricket history involving declarations or their equivalent.

THE CUMMINS DECLARATION

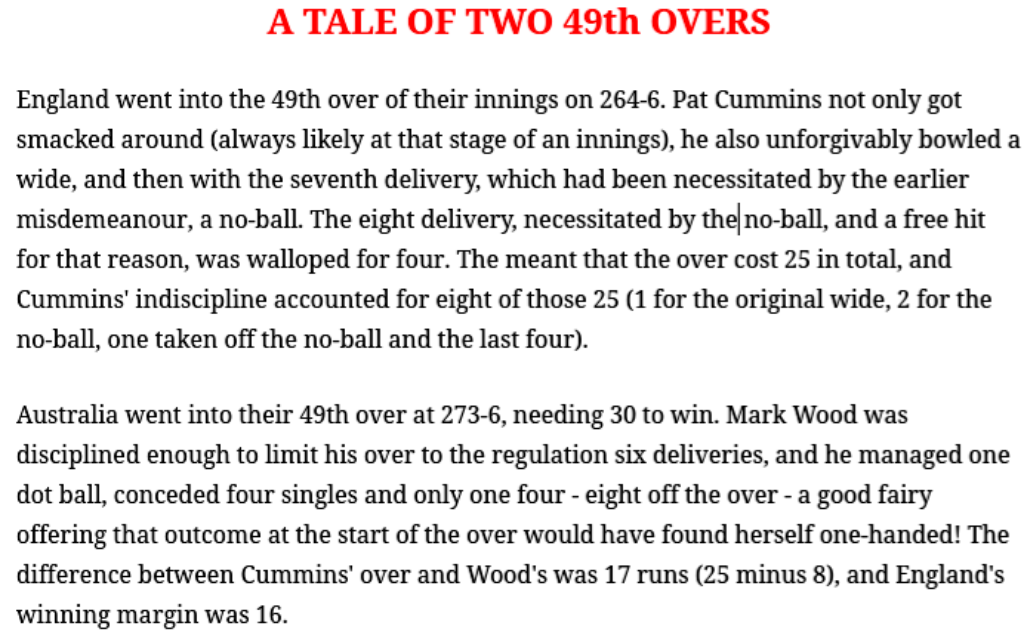

West Indies had fought back from a poor start to record a first innings score of 311, Australia then had an even worse start to their first innings, being 24-4 at one point. They also fought back hard, and reached 289-9, at which point Cummins declared, opting to look for early wickets under the lights. While declaring when still in deficit is unusual there were justifications for taking this approach. Australia were unbeaten in day/night tests, largely because they as a whole, and Mitchell Starc in particular bowl so well under the lights, so it was natural for Cummins to want to play a potential trump card. Unfortunately for Cummins Australia managed only one wicket in the mini-session under the lights that he engineered for them, and West Indies ended up winning the match by eight runs.

DECLARATIONS THROUGH THE AGES

Declarations were only allowed in the late 19th century, and two matches from the tail end of the period in which declarations were not permitted help to illustrate why.

When Surrey played Nottinghamshire in 1889 they were going well in their second innings – so well in fact that they were in danger of not having enough time left to dismiss Nottinghamshire a second time. Surrey captain John Shuter instructed his side to get themselves out quickly, and they did so. Surrey then bowled Nottinghamshire out cheaply. In 1893 England were playing Australia in a rain affected match, and England were batting with a small lead at the end of day’s play. England captain WG Grace inspected the pitch the following morning and getting back to the pavilion he told his team mates “I need you to get out quickly – we need to be bowling by 12:30 at the latest”. Grace was not the sort of skipper anyone would dare ignore, and England duly lost their remaining wickets in 20 minutes of play. Australia then collapsed on a pitch that was every bit as spiteful as WG had reckoned it would be and England won the match.

1936 – DECLARING BEHIND AND A DRAMATIC COUNTER

England were 2-0 up in an away Ashes series after two matches, and all seemed to going well when they got Australia out for 200 in the first innings of the third match. Then the rain came, turning the pitch into a vicious sticky. England limped to 76-9 before skipper Allen declared to get Australia back in again while the pitch was still misbehaving. Bradman countered by sending tailenders O’Reilly and Fleetwood-Smith in to play and miss until the close, and when O’Reilly was out before the close he sent in another tail ender, Frank Ward. All of this meant that by the time Bradman, normally number three, joined Fingleton, a regular opener, the score was 97-5, and the pitch was easing. Bradman and Fingleton put on 346 together for the sixth wicket, Bradman going on to record score for anyone batting at number seven in a test match of 270, and England were beaten by a massive margin.

1950 – DECLARATION AND COUNTER DECLARATION

The England squad for the 1950-1 Ashes arrived in Australia not expected to do much, with both batting and bowling looking questionable and the skipper Freddie Brown known to have been the third choice for that role. In the first match at Brisbane they rose magnificently to the occasion in the first innings and dismissed the Australians for 228 on a plumb pitch. Unfortunately for them it then rained, with the usual effect on uncovered pitches. At 68-7 Brown declared to get Australia in while the pitch was at its worst. Australia were 32-7, and in danger of being all out for a new all time test low, beating the 36 they had been rolled for at Edgbaston in 1902, when Hassett declared to get England back in that night. England held back Hutton for the following day, but unfortunately they did not make a great fist of surviving that evening being 30-6 by the close. The worst of many poor dismissals among those six was that of Arthur McIntyre, reserve keeper but playing that match as a batter, who was run out coming back for a fourth run. Hutton played a superb innings the following day, but England came up short.

A DECLARATION ON DAY ONE, BATTING SECOND

Surrey were going a third successive title near the end of the 1954 season when they played Worcestershire. Worcestershire were all out for 27 batting first. With Surrey 92-3 Stuart Surridge decided he wanted another go at Worcestershire that evening and declared. Laker and Lock each claimed a wicket by the end of day one, and on the second morning Worcestershire were all out for 40, and won by an innings and 25 runs, which ensured that they would retain the championship.

A STOKES SPECIAL

A few months before England toured Pakistan in late 2022 Australia had visited, and when they played at Rawalpindi they had a full bowling attack, rated among the best in the world, and took precisely four Pakistan wickets in the match. Thus, England were already well in credit by tea on day four, having dismissed Pakistan in their first innings and built an advantage of 347. At that point Ben Stokes opted to declare, a declaration that many rushed to condemn. I had not been expecting the move, but did not rush to judgement on it. Having been following the match the whole way through I knew that both evening sessions would be abbreviated due to lack of daylight, so it was not quite as generous in practice as it was in theory. England secured the victory with time for probably nine more balls, and at most 15, before the light closed in on the final day (the final wicket went to the third ball of an over, and there were nine minutes left before the time at which the light had been judged unplayable the previous day).

PHOTOGRAPHS

New on my blog: