INTRODUCTION

Today is the start of new month, and also the start of an England intra-squad warm up match at the Ageas bowl in preparation for the resumption of test cricket next week. This match is 14 vs 13, not 11 vs 11, so does not have first class status, but is significant because of what it portends and because there is a batting vacancy at no4, since Joe Root is attending the birth of his child and will then be quarantining for 14 days. Team Buttler have been put into bat by Team Stokes, and as I start this post are 119-1, with James Bracey making an early bid for the vacant batting slot having passed 50. I aim to keep my all time XIs cricket series going until the test match gets underway, when I will give that my full attention. Today’s post harks back to the early days of international cricket, inspired by my rereading John Lazanby’s “The Strangers Who Came Home”, a brilliantly crafted reconstruction of the 1878 tour of England. As a tribute to the contrasting Bannerman brothers I have pitted a team of 11 Alecs/ Alexes against 11 Charleses/Charlies/Charls.

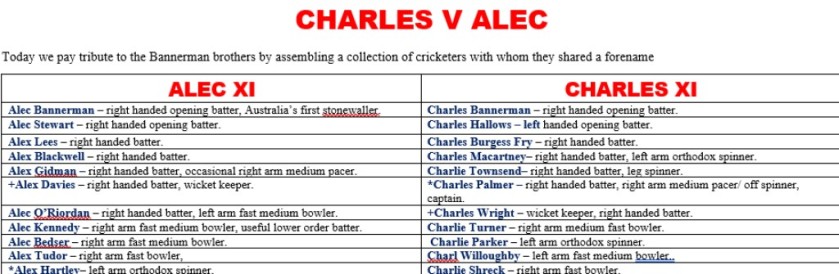

ALEC XI

- Alec Bannerman – right handed opening batter. Australia’s first stonewaller. He never managed a test century, his best being 94, while his most famous was a 91 in seven and a half hours, which included a whole uninterrupted day in which he advanced his score by 67.

- Alec Stewart – right handed opening batter. A blocker is best accompanied by someone of more attacking inclination to avoid the innings becoming entirely bogged down, and Alec Stewart fits the bill perfectly. He scored more test runs in the 1990s than anyone else, in spite of being messed around by the selectors of the time, who often used him as a wicket keeper in an effort to strengthen the batting.

- Alex Lees – right handed batter. A third recognized opener, and one who as a teenager played an innings of 275 for his native Yorkshire. He did not quite go on to scale the heights that this innings suggested he was capable of, and subsequently moved from Yorkshire to Durham.

- Alex Blackwell – right handed batter. A former captain of the Aussie Women’s team, with a fine batting record. When the commentators picked a composite team at the end of the 2010-1 Ashes Jonathan Agnew named as the token Aussie in an otherwise all English line up.

- Alex Gidman – right handed batter, occasional right arm medium pacer. Over 11,000 first class runs at an average of 36 and never got the opportunity to play for England.

- +Alex Davies – right handed batter, wicket keeper. 171 dismissals effected in 75 first class matches and a batting average of 34.55 at that level. He is better known for his efforts in limited overs cricket, where his rapidity of scoring is especially useful, but he should not be typecast as a limited overs specialist.

- Alec O’Riordan – right handed batter, left arm fast medium bowler. He played a starring role in Ireland’s dramatic victory of the West Indies at Sion Mills in 1969 and was for a long time the best all rounder that country had produced.

- Alec Kennedy – right arm fast medium bowler, useful lower order batter. He played for Hampshire for the thick end of 30 years, pretty much carrying their bowling in that period, with support from Jack Newman and Stuart Boyes.

- Alec Bedser – right arm fast medium bowler. One of the greatest bowlers of his type ever to play the game. He was taught by the all rounder Alan Peach how to grip the ball if he wanted it to go straight through rather than swinging. When Bedser tried this himself he actually found that the ball spun from leg to off, and one of the deliveries he bowled in that fashion was described by Bradman as “the best ball ever to take my wicket.”

- Alex Tudor – right arm fast bowler. With Kennedy, Bedser and O’Riordan all steady types we definitely have space for an out and out speedster, and Tudor is that man. He is actually best known for a batting effort, on his test debut against New Zealand, when he was sent in as nightwatchman and was 99 not out when England completed their victory (Graham Thorpe, who came in with victory already pretty much certain, blitzed a succession of boundaries to finish it, the second time he may have been responsible for a batter finishing unbeaten in the 90s, after the incident where Atherton declared with Hick 98 not out, and it appeared that Thorpe had failed to pass on a message from the skipper). His career was subsequently blighted by injuries and he never did get to complete a century.

- *Alex Hartley – left arm orthodox spinner. We have been short of spin options so far, but fortunately we have a world cup winning spinner to round out the XI. She has subsequently lost her England place, and given how many talented young spinners there are now in England women’s cricket it is unlikely that she will regain it, but the world cup winner’s medal cannot be taken away from her.

This side has an excellent top six including a decent quality keeper, a genuine all rounder at seven and four varied bowlers. The side is short of spinners, with Hartley the only real option in that department, but O’Riordan’s left arm and Bedser’s one that spun from leg to off means that this is far from being a monotonous bowling attack. The fact that there are five front line bowlers allows for Tudor being used in short bursts at top pace.

NOT PICKED

Hampshire stalwart Alec Bowell just missed out. Alex Loudon with a batting average of 31 and a bowling average of 40 was the reverse of an all rounder, and although an off spinner would have been useful he had to be ignored. Alex Barnett, a left arm spinner, did not have a record to warrant displacing a world cup winner. Alex Hales is mainly a white ball player, and is also under a cloud because of his personal conduct.

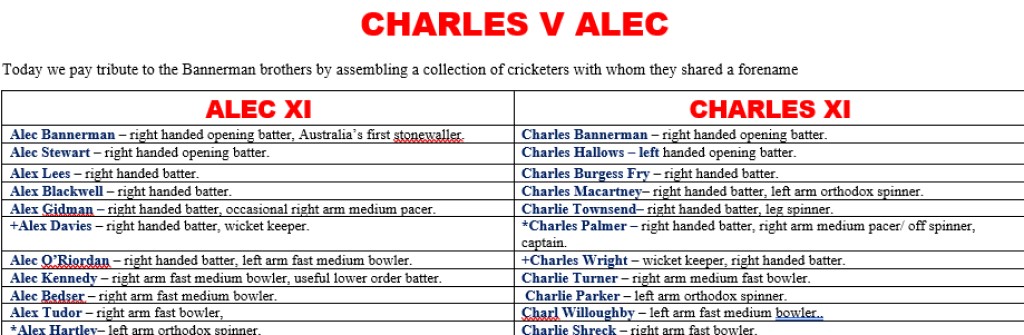

CHARLES XI

- Charles Bannerman – right handed opening batter. Scored 165 in the first innings of the first test, in an all out tally of 245, still the biggest proportion of a test innings ever scored by one person. In 1878 he became the first Australian to score a century in England, having already done so in New Zealand, and he would later make it a quadruple by racking up a ton in Canada en route back to Australia.

- Charles Hallows – left handed opening batter. An excellent counterpoint to the all attacking right hander Bannerman, since he was more defensively inclined. He opened the batting for Lancashire in their greatest period in the 1920s, and in 1928 he became the third and last player to score 1,000 first class runs actually in the month of May (Bradman, twice, Edrich, Hayward, Hick and Glenn Turner each reached 1,000 first class runs in an English season before the start of June, but all benefitted from games played in April) exactly one year after Walter Hammond had equalled the 1895 achievement of WG Grace. At the start of May 30th 1928 Hallows was on 768 runs for the season, Lancashire won the toss and batted, and by the close Hallows had reached 190 not out. He got those 42 runs on the morning of May 31, and then a combination of exhaustion and relief caused him to snick one behind and he was out for 232, with his aggregate precisely 1,000 for the season. In all he scored 55 first class hundreds and averaged 40 with the bat in his first class career.

- Charles Burgess Fry – right handed batter. A third recognized opener. In amongst all the other extraordinary things he did in his life he amassed 94 first class centuries, and recorded a first class average of 50. When his career started no one had ever scored more than three successive first class hundreds, and in 1901 he broke that record and went on to make it six in succession before the sequence finally ended, a record which has been equalled by Bradman and Procter but never surpassed.

- Charles Macartney – right handed batter, left arm orthodox spinner. In 1926, at the age of 40, he scored centuries in each of three successive tests (to no avail for his side, as those games all finished in draws and England won the final match at The Oval to take the Ashes). Five years earlier he had hit Nottinghamshire for 345 in 232 minutes, the highest score by an Australian on tour of England.

- Charlie Townsend – right handed batter, leg spinner. In 1894 he became only the second player to score 2,000 first class runs and take 100 first class wickets in a season.

- *Charles Palmer – right handed batter, medium pace bowler/ off spinner, captain. One of his bowling stints gave him a shot at the record books – he had figures of 8-0, and he he stopped bowling at that point he would have been indelibly there. He kept going, and the spell was broken, and he ended up having to settle for a mere 8-7 (behind Laker 8-2, Shackleton 8-4, Peate 8-5 and level with George Lohmann who achieved his 8-7 in a test match)! He scored just over 17,000 first class runs at 31, and his 365 wickets cost 25 each.

- +Charles Wright – wicket keeper, right handed batter. He played in the late Victorian era, scoring almost 7,000 first class runs and making 235 dismissals of which 40 were stumpings.

- Charlie Turner – right arm medium fast bowler. Joint quickest ever to the career landmark of 100 test wickets, achieved in his 17th match. Only bowler ever to take 100 first class wickets in an Australian season.

- Charlie Parker – left arm orthodox spinner. The third leading first class wicket taker ever, with 3,278 scalps, and yet only one England appearance. At Leeds in 1926 he was in the 12 but left out on the morning of the match.

- Charl Willoughby – left arm fast medium bowler. An excellent record for Somerset in county cricket, and his left handedness is a useful variation.

- Charlie Shreck – right arm fast bowler. The 6’7″ Cornish born quick bowler took 577 first class wickets at 31.80, a respectable rather than outstanding record. His pace and height will be useful in this attack.

This team has a strong top six, a keeper and four varied bowlers. Willoughby, Shreck and Turner are a fine pace attack, while Parker, Townsend and the more occasional stuff of Palmer offer plenty of spin.

MISSING

Charlie Barnett had a fair claim on opening slot, but I felt that with the attacking Bannerman claiming one slot someone steadier was required. Similarly, given the overload of available openers of quality I could not find a place for Charlotte Edwards. Charlie McGahey who played for Essex in the early 20th century had a good record as a middle order batter, but he did not the bowling of Townsend or the combined bowling and captaincy of Palmer. Australian keeper Charles Walker might have had the gloves instead of Wright. Charl Langeveldt had a decent record as a right arm medium fast bowler, but Willoughby’s left handedness worked in his favour. Charles Dagnall, now well known as a commentator, did not have a particularly special record as a medium fast bowler for Leicestershire and Warwickshire, and so although his name is well known I could not pick him.

THE CONTEST

We have two well balanced sides here, although the Charles XI has the better balanced bowling unit, and a more powerful engine room to its batting (Hallows, Fry, Macartney), though the Alec XI bats deeper with Bedser at nine and Tudor at 10.

LOOKING AHEAD

Buttler’s XI are currently going very well, with Bracey now in the 80s and Dan Lawrence having made a rapid start being on 32 off 38 balls (he would be my pick for the no4 slot vacated by Root, so I am especially pleased to see that he is going well. The plan for this series, as mentioned earlier, is to keep it going until the test match gets underway. I am also going to float a speculative kite: there is enough material in this series of blog posts to fill a book if people would be interested in reading it. Bracey has just gone, c Foakes b J Overton 85, to make it 196-3.

PHOTOGRAPHS

My usual sign off…