INTRODUCTION

Welcome to the latest of my variations on an ‘All Time XIs‘ theme. Today for only the second time since starting this series I am doing a test XI, and I my choice puts me in the firing line of 1.3 billion avid cricket fans – yes it is India in the spotlight today. I am going to begin from players whp featured in the time that I have been following the game, and will then move to on the all-time element of the selection.

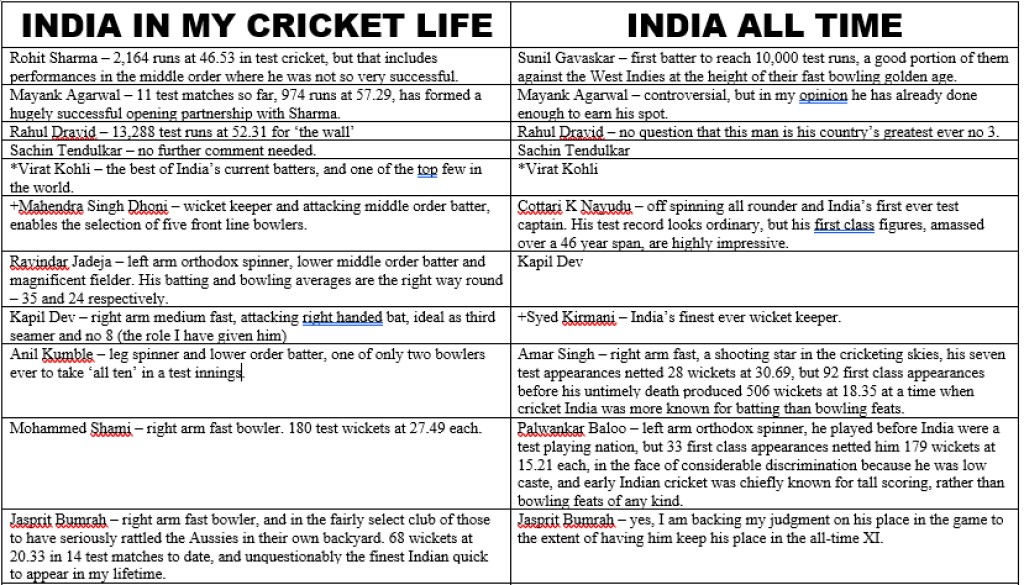

INDIA FROM MY CRICKET LIFETIME

For this element of the post I have set my cut off point at that 1990 series in England – I caught snatches of the 1986 series, but the 1990 one is the earliest involving India of which I can claim genuine recollection (England should have visited India in 1988-9 but that tour was cancelled for political reasons).

- Mayank Agarwal – 11 test matches, 17 innings, 974 runs at 57.29, no not outs to boost the average. He has made a sensational start at the highest level, and is also part of a tremendously successful opening partnership with…

- Rohit Sharma – 2,164 runs at 46.54 in test cricket sounds good but a little short of true greatness. However, Sharma was initially played at test level as a middle order batter, and his results since being promoted to the top of the order have been utterly outstanding.

- Rahul Dravid – 13,288 test runs at 52.31 for ‘the wall’. In the 2002 series, he and Michael Vaughan of England took it in turns to produce huge scores. Dravid assisted in one of test cricket’s greatest turnarounds in 2001, when India were made to follow on and emerged victorious by 171 runs, and I shall have more to say about this match in due time.

- Sachin Tendulkar – more runs and more hundreds (precisely 100 of them) in international cricket than anyone else in the game’s history. He was one of the few batters of his era who could genuinely claim to have had the whip hand on Shane Warne. I first saw him in that 1990 series when he was 17 years of age, and his personal highlights included a maiden test century and an astonishing running catch (he covered at least 30 metres to get to the ball).

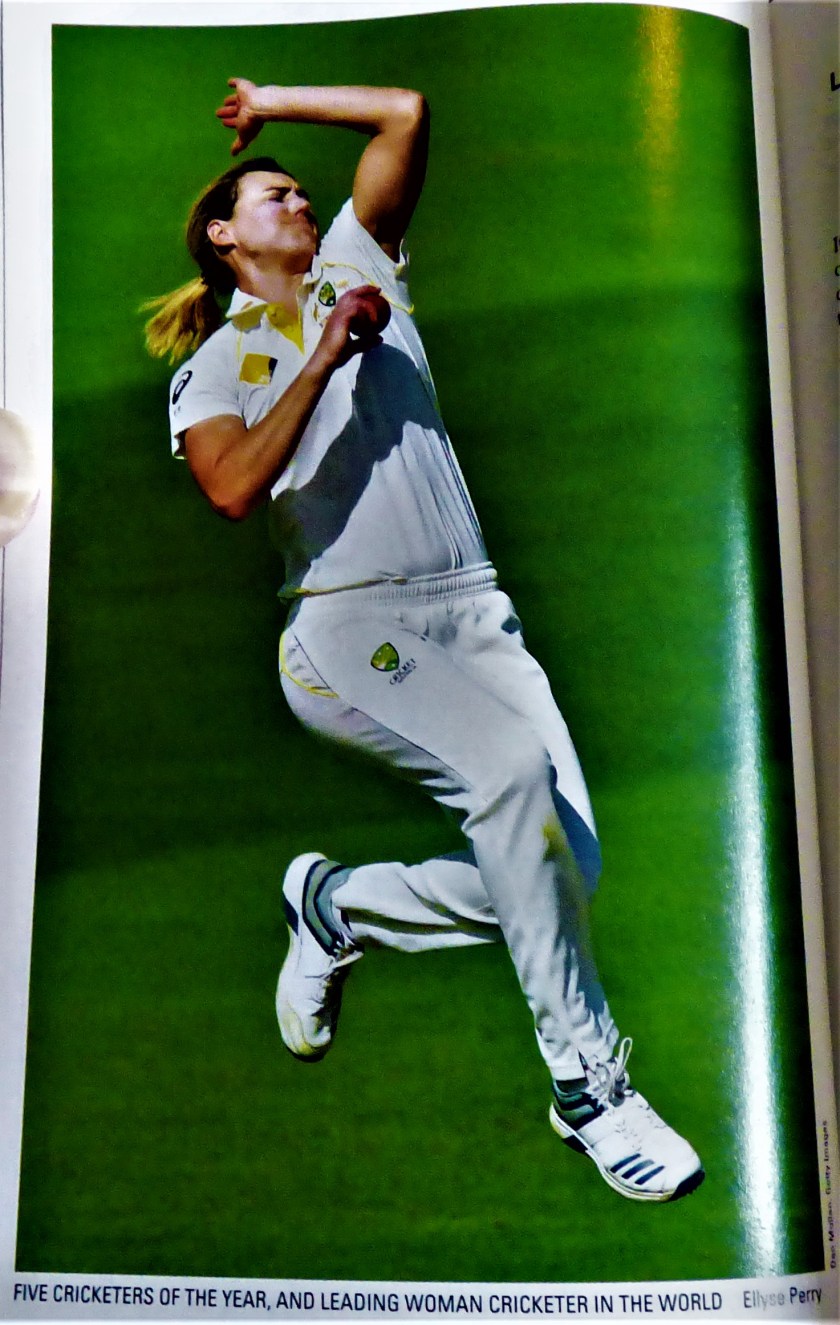

- *Virat Kohli – one of the top few batters in the world today (the Aussies Smith and Labuschagne both have higher test averages, and Kiwi skipper Kane Williamson bears comparison, and heterodox as I am about such matters I would also when it comes to long form batting throw Ellyse Perry into the mix), and has certainly already achieved enough to be counted among the greats.

- +Mahendra Singh Dhoni – wicket keeper and dashing middle order batter. Of the contenders for the gloves he alone has a batting record the enables me to select five front line bowlers.

- Ravindra Jadeja – left arm orthodox spinner, lower middle order batter and superb fielder. His averages are the correct way round (35 with the bat and 24 with the ball).

- Kapil Dev – right arm medium fast, attacking lower middle order batter. He spent much of his career with no pace support whatsoever, having to attempt to be the spearhead of an attack that was often moderate. At Lord’s in that 1990 series he played an innings that should have saved his side from defeat, though it did not. Facing 653-4 declared (Gooch 333) India were 430-9, with Narendra Hirwani, a fine leg spinner who had captured 16 West Indian wickets on test debut but a genuine no11 bat at the other end, when Kapil faced off spinner Eddie Hemmings. There were four balls left in the over, and Kapil’s task was to score 24 to avert the follow-on. He proceeded to hit each of those last four balls for six to accomplish the task. Hirwani, as predicted, did not last long, and England had a lead of 199. Gooch crashed a rapid 123 in that second England innings (a record 456 runs in a test match, the triple century/ century double was subsequently emulated by Sri Lanka’s Kumar Sangakkara), and India collapsed in the fourth innings of the match, giving England what turned out to be the only victory of the series.

- Anil Kumble – leg spinner, lower order batter. One of only two bowlers, the other being Jim Laker, to have taken all 10 wickets in a test innings, and the third leading test wicket taker of all time.

- Mohammed Shami – right arm fast bowler. India has not generally been known for producing out and out quick bowlers, but Shami’s 180 wickets at 27.49 are a testament to his effectiveness.

- Jasprit Bumrah – right arm fast bowler, 14 test matches, 68 wickets at 20.33. Save for when the West Indies were in their pomp visiting fast bowlers have rarely been able to claim to have blitzed the Aussies in their own backyard. Bumrah, who virtually settled the destiny of the Melbourne test of 2018, and with it the Border-Gavaskar trophy, with a devastating spell in the Australian first innings is one of the exceptions.

This combination boasts a stellar top five, a wicket keeping all rounder at six, and five varied and talented bowlers, the first three of whom can all contribute with the bat as well. I believe that Kapil Dev as third seamer in a top quality attack rather than spearhead in a moderate one, which was too often the role he had to play, would be even finer than he was in real life. Now we look at the…

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

This section begins with an explanation (nb not an excuse, there being in my opinion nothing to excuse) of one of my choices:

JADEJA V ASHWIN

The choice for the second spinner role was really between these two, and there will be many wondering at the absence of Mr Ashwin. Here then is the explanation:

Jadeja – 1,869 test runs at 35.24, 213 test wickets at 24.62.

Ashwin – 2,389 test runs at 28.10, 365 wickets at 25.43

Jadeja outdoes Ashwin both with bat and ball, which is why he gets the nod from me.

Now we on to the other honourable mention to get his own subsection…

THE VERY VERY SPECIAL INNINGS

Against the mighty Aussies in 2001 Vangipurappu Venkata Sai Laxman came in in the second innings with India having followed on and already four down and still some way behind. He proceeded to score 281, at the time the highest individual test score ever made by an Indian, India reached 657-7 declared (Dravid 180 as well), and with 383 to defend rolled Australia for 212 to win by 171 runs. India took the next match and with it the series as well – Laxman in one brilliant, brutal innings had upended the entire series. Laxman finished his career with 8,781 test runs at 45.24, a very respectable record, but not quite on a par with the middle order batters I actually selected – India has always been hugely strong in this department.

OTHER HONOURABLE MENTIONS

Two other opening batters besides my chosen pair featured in my thoughts – Virender Sehwag, scorer of two test triple hundreds, and a shoo-in for Agarwal’s partner had I decided not go with the known effective partnership, and Navjot Singh Sidhu, an attack minded opener in the 1990s, who had a fine test record, but not quite fine enough to make the cut. For much of my time as a cricket follower India have struggled to find openers, often selecting makeweights to see of the new ball before the folks in the middle order take control (Deep Dasgupta, Shiv Sunder Das, Manoj Prabhakar and Sanjay Bangar, the last two of whom also served as opening bowlers are four examples that I can remember). In the middle of the order Mohammed Azharruddin, Sourav Ganguly and Vinod Kambli were three of the highest quality performers to have missed out, although the first named is of course tainted by his association with match fixing. Cheteshwar Pujara was a candidate for the no 3 slot I awarded to Dravid, but for me ‘the wall’ just shades it. Kiran More, Nayan Mongia, Rishabh Pant and current incumbent Wriddhiman Saha are a fine foursome of glove men all of whom would have their advocates. Among the spinners I passed over were Chauhan and Raju in the 1990s, Harbhajan Singh in the early 2000s and Narendra Hirwani the leg spinner who took 16 on debut but did little else in his career. Also, while mentioning Indian spinners who I have been privileged to have witnessed in action I cannot fail to mention Poonam Yadav, who nearly bowled her country to this years T20 world cup. The seam bowling department offered fewer alternatives, but Javagal Srinath, the first Indian bowler of genuine pace who I ever saw, left arm fast medium Zaheer Khan and dependable fast medium Bhuvneshwar Kumar would all have their advocates, but I had already inked Kapil in the for role of third seamer and wanted the two out and out quick bowlers of the current era as my shock bowlers.

INDIA ALL TIME

I will only mention the players I have not already covered, before listing the batting order in full and moving on to the honourable mentions.

- Sunil Gavaskar has a test record that absolutely demands inclusion – he was the first to 10,000 test runs and made a good portion of those runs against the West Indies when they were stacked with fast bowlers. I could not include him in the team from my time as a cricket follower, because he was finishing his great career just as my interest in cricket began to develop. I saw one reminder of his past glories, when he batted for The Rest of The World v the MCC in the MCC Bicentenary match and made a chanceless century, never giving the bowlers a sniff.

- Cottari K Nayudu was an off spinning all rounder and India’s first ever test captain. His seven test matches left him with a modest looking record at that level, but his first class record, built up over a span of 46 years looks very impressive indeed.

- Syed Kirmani is generally considered to be have been India’s greatest wicket keeper.

- Amar Singh was a shooting star across the cricketing sky, India’s first great fast bowler, and for many years the only one of international repute that his country produced. His seven test appearances produced 28 wickets at 30.69, but it is record in 92 first class appearances, 506 wickets at 18.35 that gets him the nod from me, especially given what cricket in India was like in that period.

- Palwankar Baloo was a left arm spinner who played his cricket before India was a test playing nation, and had to contend with huge prejudice as a member of a low caste. Unlike the various Jam Sahebs, Maharajas and Nawabs who were able to strut their stuff in English county cricket he had to settle for those games people would pick him for in India. The 33 games he played at first class level yielded him 179 wickets at 15.31 each. Although I am open to correction on this I believe he is also the only first class cricketer to share a name with a character from the Jungle Book (Baloo is the big brown bear who teaches Mowgli the law of the jungle in Rudyard Kipling’s magnum opus).

Thus my all-time Indian team in batting order is: 1)Sunil Gavaskar 2)Mayant Agarwal who in spite of his short career to date holds his position 3)Rahul Dravid 4)Sachin Tendulkar 5)*Virat Kohli 6)Cottari K Nayudu 7)Kapil Dev 8)+Syed Kirmani 9)Amar Singh 10)Palwankar Baloo 11)Jasprit Bumrah

This combination features a stellar top five, 6,7 and 8 all capable of useful runs, and three superb specialist bowlers. The wicket keeper is top drawer. The bowling attack features two genuinely fast bowlers, Kapil Dev as third seamer and two contrasting spinners in Baloo (left arm orthodox) and Nayudu (off spin).

HONOURABLE MENTIONS

Other than those mentioned earlier the only other opener I considered was Vijay Merchant, who had the second highest first class average of anyone at 71.22. His test average was a mere 47 however, a massive decline on his first class output for reasons I shall go into later, and for this reason I reluctantly ruled him out. In the middle order Vijay Hazare, Pahlan Umrigar and Gundappa Viswanath would all have their advocates, will I also had to ignore the possessor of the 4th highest first class score in history, Bhausaheb Nimbalkar. Among all rounders the biggest miss was Mulvantrai Himmatlal ‘Vinoo’ Mankad, who completed the double of 1,000 runs and 100 wickets in test cricket in his 23rd match (only Botham has required fewer), but I was determined to select Baloo, which meant that there would be less scope for Mankad’s left arm spin, so in the interests of balance I left him out. My view on the mode of dismissal named after him is that it is the batter who is trying to gain an unfair advantage by leaving the ground earlier, and if the bowler spots and runs them out well done to them, although delaying before going into delivery stride in the hope of catching a batter napping is taking things a little too far. Dattu Phadkar, a middle order batter who was often used as an opening bowler was another who could have been considered. With all due respect to Messrs Bedi, Prasanna and Venkataraghavan who each had more than respectable records the only one of the great 1970s spinners I really regretted not being able to find a place for was Bhagwath Chandrasekhar the leg spinner who was a genuine original. His right arm was withered by polio, and that was the arm he bowled with. Among specialist pace bowlers there are, as I have previously indicated, few contenders, but Chetan Sharma had has moments in the 1980s. It is now time for…

A CODA ON THE DOMINANCE OF THE BAT IN INDIAN CRICKET

For a long time first class matches in India were timeless, which is to say they were played out until a definite result was reached. Some of the scores were astronomical, with the only two first class matches to have had aggregates of over 2,000 runs both played in India. I will use one match as a case study:

BOMBAY V MAHARASHTRA 1948

This match featured in Patrick Murphy’s “Fifty Incredible Cricket Matches”, and he used a phrase about matches such as this one that I just love “a meaningless fiesta for Frindalls” (William Howard Frindall, aka ‘Bearders’, was the second chronologically of two legendary statisticians to have initials WHF, the other being William Henry Ferguson). Bombay scored 651-9 declared in their first innings, Maharashtra made 407 in response, and Bombay declined to enforce the follow-on, racking up 714-8 declared at the second time of asking to set Maharashtra 959 to win. Maharashtra managed 604 of these, losing by 354 runs in a match that saw 2,376 runs and 37 wickets, the highest aggregate for any first class match ever. Three batters notched up twin centuries, Uday Merchant (nb Uday, not the famous Vijay) and Dattu Phadkar for Bombay, and Madhusudan Rege for Maharashtra. Phadkar was a test regular, Rege played one test match in which he aggregated 15, and even in first class cricket averaged only 37 in all, while Merchant had a first class average of 55.78 but was never picked for a test match, and there were three other individual centuries. What this kind of thing meant was that Indian bowlers tended to operate under a collective inferiority complex, while the batters would flounder any time they faced other than a shirt front. Fred Trueman, who bowled against Pahlan Umrigar in the 1952 test series (at his retirement Umrigar held a fistful of Indian test records), and claimed that there were times when he was bowling and the square leg umpire was nearer the stumps than Umrigar, the batter, and while this story may have grown in the telling, it would have been an exaggeration rather than a complete invention. This is why I would need a lot of convincing of the actual merits of some of those who had fine looking batting records in those years, while any bowler with a good looking record is likely to get huge credit, and it is one reason why I make no apology for my choices of Amar Singh and Palwankar Baloo in my All Time Indian XI.

LINKS AND PHOTOGRAPHS

We have reached the end of our journey through Indian cricket, and it only remains to put in a couple of links before applying my usual sign off. First, finishing with the cricket I draw your attention to the pinchhitter’s latest offering, which will certainly repay a read. Finally, a splendid piece on whyevolutionistrue in defence of governor Andrew Cuomo who has been pilloried by religious zealots for daring to not give god full credit for such success as has been had in the fight against Covid-19. And now, in my own distinctive way it is time to call ‘Time’: