INTRODUCTION

After completing my look at the English first class counties yesterday (click here to visit a page from which you can access all 18 of those posts) I am now moving on to the next stage of this series. In this post I am going to attempt to explain more of my thinking about selection. I will begin by presenting an Australian XI of players from my time following cricket, which I am taking as starting from the 1989 Ashes (I saw odd bits from the 1985 series and heard about the 1986-7 series but 1989 was the first I can claim really direct memories of. Before moving on to the team that many of my fellow Poms would be watching from behind the sofa there is one other thing to do…

THE RECEPTION OF MY FIRST 18 POSTS (WITH A NOD TO THE PINCHHITTER)

Yesterday I shared my All Time XIs for the counties on twitter. The feedback was very interesting, and mainly tendered in the right spirit. The PinchHitter, who sends out a daily email to those who sign up for it was today kind enough to include a reference to this endeavour in today’s email, which you can view here. Everyone’s opinions differ, and so long as suggestions are made with constructive intent I will not complain, though I would ask that you suggest who should be left out to accommodate your favoured choices. I am bound in an endeavour of this nature to fail to flag up people who merit attention – tthere are vast numbers of players to be considered when doing something like this.

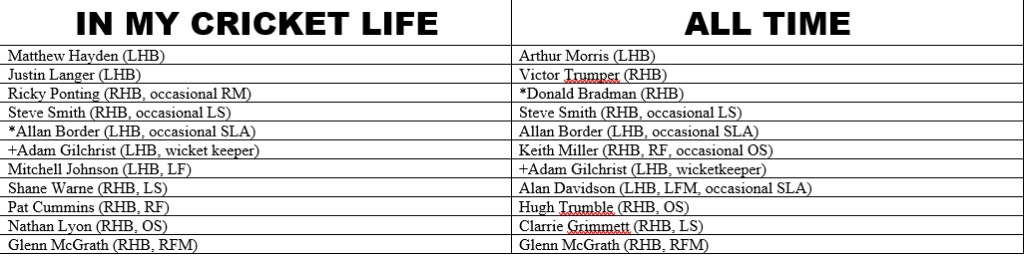

AUSTRALIA IN MY CRICKET LIFE XI

- Matthew Hayden – an attack minded left handed opener who was very successful over a number of years. He had a horrible time in the first four matches of the 2005 Ashes, but bounced back with 138 in the fifth match at The Oval. In Brisbane in 2002 he cashed in on Nasser Hussain’s decision to field first by scoring 197, and then adding another ton in the second innings.

- Justin Langer – a different style of left handed opener to Hayden, his most regular partner, Langer was no less effective at the top of the order. His greatest performance was a score of 250 at the MCG. He played in the county championship for Middlesex and Somerset.

- Ricky Ponting – a right hander whose natural inclination was to attack but who could also produce a defensive knock at need. Although he had one very poor Ashes series, in 2010-11 his overall record demanded inclusion.

- Steve Smith – a right hander, with an even better average (to date), than Ponting. He was tarnished by his involvement in sandpapergate, but his comeback in the 2019 Ashes showed that while he cannot be trusted with a leadership position his skill with the bat remains undminished.

- *Allan Border – a left handed middle order bat who was the first to 11,000 test runs, also an occasional left arm spinner who did once win his country a match with his bowling (match figures of 11-96 against the West Indies in 1988). For the first 10 years of his long career he was a mediocre side’s only serious bulwark against defeat, but in the last years of his career he was part of the first of a succession of great Australian teams. The role he played as captain in Australia’s transformation from moderate to world beaters was an essential part of the story of the ‘Green and Golden Age’ and I recognize it as such by naming him captain of this side.

- +Adam Gilchrist – attacking left handed middle order bat (opener in limited overs cricket) and high quality wicket keeper. One of the reasons that England won the 2005 Ashes was that they were able to keep him quiet (highest score of the series 49 not out), the only time in his career any side managed that. At Perth in the 2006-7 series, immediately following a victory at Adelaide after England had made 550 in the first innings and then did a collective impression of rabbits in headlights against Warne in the second, he smashed a century off 57 balls, then the second fastest ever test century in terms of balls faced.

- Mitchell Johnson – left arm fast bowler and attacking left handed lower middle order bat, also the ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ of 21st century test cricket. In the 2010-11 Ashes the ‘Hyde” version predominated, save for one great match at Perth, struggling to such an extent in his other games in that series that he probably scared his own fielders more than the England batters! The ‘Jekyll’ version was on display in the 2013-14 Ashes, when he bowled as quick as anyone in my cricket following lifetime, was also accurate, and scared the daylights out of the England batters, taking 37 wickets in the series and being the single most important reason for the 5-0 scoreline that eventuated.

- Shane Warne – leg spinner and attacking right handed lower order bat – one of the two greatest spinners I have seen in action (Muttiah Muralitharan being the other). From the moment that his first ball floated in the air to a position outside leg stump and then spun back to brush Mike Gatting’s off stump at Old Trafford in 1993 he had a hex on England, becoming the first bowler ever to take 100 test wickets in a country other than his own. In the 2005 Ashes, when England regained the urn after 16 years, he took 40 wickets and scored 250 runs in the series. His only blot in the series came at The Oval when he dropped an easy chance offered by Kevin Pietersen, which allowed that worthy to play his greatest ever innings and secure the series. He took over 700 test wickets (the exact figure is open to argument, since some of his credited wickets were taken in an Australia v Rest of The World game, and earlier ROW games organized when South Africa were banished from the test scene are not counted in the records). He also scored more test runs than anyone else who never managed a century, 3,154 of them.

- Pat Cummins – right arm fast bowler, right handed lower order bat. Injuries hampered his progress (he first appeared on the scene as a 17 year old, but he has still done enough to warrant his inclusion. At the MCG in 2018, when Jasprit Bumrah rendered the Aussies feather-legged with a great display of fast bowling, Cummins took six cheap wickets of his own in India’s second innings, not enough to save his side, who lost both match and series, but enough to demonstrate just how good he was, a fact that he underlined in the 2019 Ashes.

- Nathan Lyon – off spinner and right handed tail end bat. One of only three spinners of proven international class that Australia have produced in my time following cricket (Stuart MacGill, a leg spinner, is the third). In the first match of the 2019 Ashes he cashed on Steve Smith’s twin tons by taking 6-49 in the final innings of the game.

- Glenn McGrath – right arm fast medium bowler and right handed tail end bat. Australia lost only one Ashes series with McGrath in the ranks, and he was crocked for both of the matches they ,lost in that series. I tend to be a bit wary of right arm fast mediums having seen far too many ineffective members of the species toiling for England over the years but this man’s record demands inclusion. In that 2005 Ashes series he was the player of the match that his side did win – his five cheap wickets after Australia had been dismissed for 190 in the first innings wrenched the initiative back for the Aussies and they never relinquished it. He is at no11 on merit, but even in that department he is a record breaker – more test career runs from no 11 than anyone else.

This combination comprises a stellar top five, a wicket keeper capable of delivering a match winning innings and a strong and varied bowling attack – left arm pace (Johnson), right arm pace (Cummins), right arm fast medium (McGrath), leg spin (Warne) and off spin (Lyon) with Border’s left arm spin a sixth option if needed. It also has a tough and resourceful skipper in Border.

BUILDING THIS COMBINATION

Australia in the period concerned have not had a world class all rounder – the nearest approach, Shane Watson, was ravaged by injuries and although he delivered respectable results with the bat his bowling was not good enough to warrant him being classed as an all rounder. I could deal with this problem by selecting Gilchrist as a wicket keeper and assigning him the traditional all rounders slot (one above his preferred place admittedly), which is what got him the nod over Ian Healy, undoubtedly the best pure wicket keeper Australia have had in my time following the game. A more controversial option would have been to borrow Ellyse Perry from the Australian Women’s team and put her at no six. Having opted for Gilchrist the question was then whether I wanted extra batting strength or extra bowling strength, and in view of the batters I could pick from and the need to take 20 wickets to win the match I opted for an extra bowling option – those who have studied my county “All Time XIs” will have noted that I always made sure they had plenty of depth and variety in the bowling department – I want my captains to be able to change the bowling, not just the bowlers. Warne and Lyon picked themselves for the spinners berths, with the coda that if the match was taking place in India Warne would have to be dropped and someone else found as he was expensive in that country (43 per wicket). Australia in this period has had two left arm quick bowlers who merited consideration, Johnson and Mitchell Starc. I opted for Johnson, as Johnson at his best, as seen in the 2013-14 Ashes was simply devastating. McGrath picked himself. For the final bowling slot I had an embarrassment of riches to choose from. I narrowed the field by deciding that I was going to pick a bowler of out and out pace. Brett Lee’s wickets came too expensively, Shaun Tait does not have the weight of achievement. I regard Cummins at his best as a finer bowler than either Josh Hazlewood or James Pattinson, so opted for him.

Turning attention to the batting, Langer and Hayden were a regular opening pair, and I did not consider either Mark Taylor or David Warner who both have great records to have done enough to warrant breaking an established pairing. Border got the no 5 slot and the captaincy because of his great record as both batter and captain and the fact that Ponting and Smith whose claims were irrefutable are both right handers. If I revisit this post in a few years I fully expect Marnus Labuschagne to be in the mix – he has made an incredible start to his test career. Adam Voges averaged 61.87 in his 20 test matches, but his career only spanned a year and a half, and a lot of the opposition he faced was weak – and in the heat of Ashes battle he failed to deliver, scoring only two fifties and no century in the series, which is in itself sufficient reason not to deem him worthy of a place. He never played in an Ashes match, the ultimate cauldron for English and Australian test cricketers, and so that average not withstanding cannot truly be considered a great of the game. The Waugh twins both had amazing test records, especially Steve, but such has been Australia’s strength in the period concerned that they cannot be accommodated.

TURNING THIS INTO AN ALL TIME XI

For me Smith and Border of the front five hold their places. Ponting would be a shoo-in for the no3 slot in almost any other team one could imagine, but for true if cruel reason that he is only the second best Australia have had in that position he loses out, with Donald Bradman (6,996 test runs at 99.94) getting the no 3 slot. At no six we now have a genuine all rounder, Keith Miller (George Giffen, once dubbed “the WG Grace of Australia”, Monty Noble and Warwick Armstrong also had superb records), with Gilchrist retaining the gloves and now dropping to no 7. There is a colossal range of bowling options, out of which I go for Alan Davidson (186 test wickets at 20.53 and a handy man to have coming in at no 8), Hugh Trumble, an off spinner whose tally of 141 Ashes wickets was a record over 70 years, and who twice performed the hat trick in test matches at the MCG, in “Jessop’s Match” at The Oval in 1902 he scored 71 runs without being dismissed and bowled unchanged through both England innings, collecting 12 wickets, comes in at no 9, Clarrie Grimmett the New Zealand born leg spinner who captured 216 wickets in just 37 test matches gets the no 10 slot and Glenn McGrath retains his no 11 slot. This team has a stellar top five, an all-rounder at six, a fine wicket keeper and explosive batter at no 7 and a very varied and potent line up of bowlers. Why Grimmett ahead of Warne? Grimmett in both test and first class cricket (he took more wickets in the latter form than anyone else who never played county championship cricket) averaged a wicket per match more than Warne.

At the top of the batting order I have replaced Hayden and Langer with Arthur Morris, a left handed opener who Bradman rated the best such that he ever saw and Victor Trumper, right handed batting hero of the early 20th century. In 1902 at Old Trafford, when England needed to keep things tight on the first morning until the run ups dried sufficiently for Bill Lockwood to be able to bowl Trumper reached his century before lunch, and since Australia won that game by just three runs this was a clearly defined match winner.

Australia has had a string of top class glove men down the years – Blackham who played in each of the first 17 test matches, Bert Oldfield, Don Tallon, Wally Grout, Rodney Marsh and Ian Healy are some of the best who appeared at test level, but none of them offer as much as Gilchrist does with the bat.

There are an absolute stack of legendary bowlers who have missed out, likewise batters – I will not attempt a listing these, but everyone who wants to is welcome to mention their own favourites.

FINAL THOUGHTS

This has been a very challenging exercise, but also a very enjoyable one. As for my All Time Aussie XI, not only would I not expect anyone else to agree with all my picks, I might well pick different players next time – there are a stack of players one could pick and be sure of. The one from my cricket following life (remember that start point of the 1989 Ashes) has fewer options, but again, it is probable that with the options available even in that period, no one else would pick the same XI that I have. If you plan to suggest changes please indicate who your choices should replace, and please consider the balance of the side when making your choices.

PHOTOGRAPHS

Our little look at the oldest enemy is over, and it remains only for my usual sign off…